“Directing attention toward where it needs to go is a primal task of leadership.” – Dan Goleman

Our ability to focus is under siege now, more than at any time in recorded history. The level of distraction through technology and social communication is unprecedented – and not just for millennials. It is imperative for leaders to grasp the fundamental importance of directing focus where it needs to go.

Focus paves the way for the development of Emotional Intelligence.

Focus is a foundational skill for emotional and social intelligence. Without it we are distracted, directionless, and disconnected from the world around us. This has deep implications for leadership. Indeed, the ability to listen, and pay attention meaningfully is critical to nearly every metric that matters in the workplace.

Cumulatively, in the U.S., we check our smartphones more than 9 billion times per day (Deloitte 2017). We reach for our phones, or look at our smart devices in meetings, while waiting in line and even in the middle of a conversation with a colleague. Much of this behavior is automatic. Everyone understands the pull of attention with the intermittent gratification of a text or tweet – and though we may not fully realize or admit it, we struggle with this at work, and at home. At times, it can feel hopeless, but it need not.

We can grow the muscle of attention regulation with small daily practices.

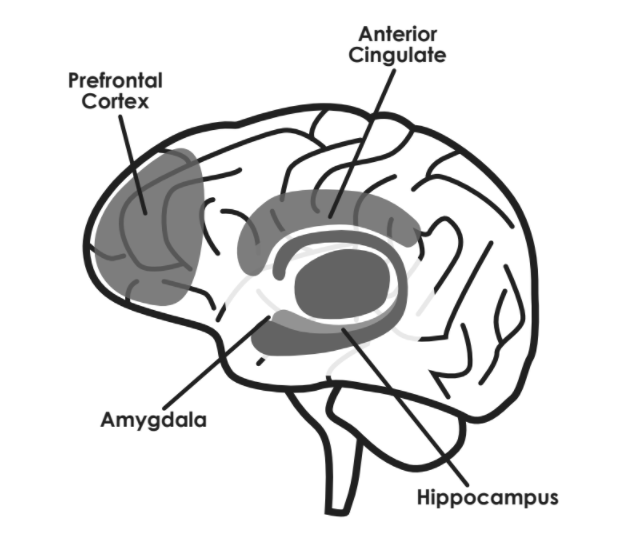

Developmental psychologists tell us that our ability to witness our own minds—our thoughts and feelings—resides in networks mainly located in the brain’s executive centers in the prefrontal cortex, just behind the forehead. Strong, disruptive emotions, like anger or anxiety, flow from circuitry lower in the brain, the limbic system (the primary structures within the limbic system include the amygdala and hippocampus). The brain’s capacity for “just saying no” to these emotional impulses takes a leap in growth during ages five to seven and increases steadily from there (though it tends to lag a bit in the emotional centers during the teen years).

The ability to be mindful of impulse—to stay focused and ignore distractions—can be enhanced by the right guidance, and by consistent practice. Mindfulness meditation practices are an excellent, always accessible, and free, method to strengthen our focus.

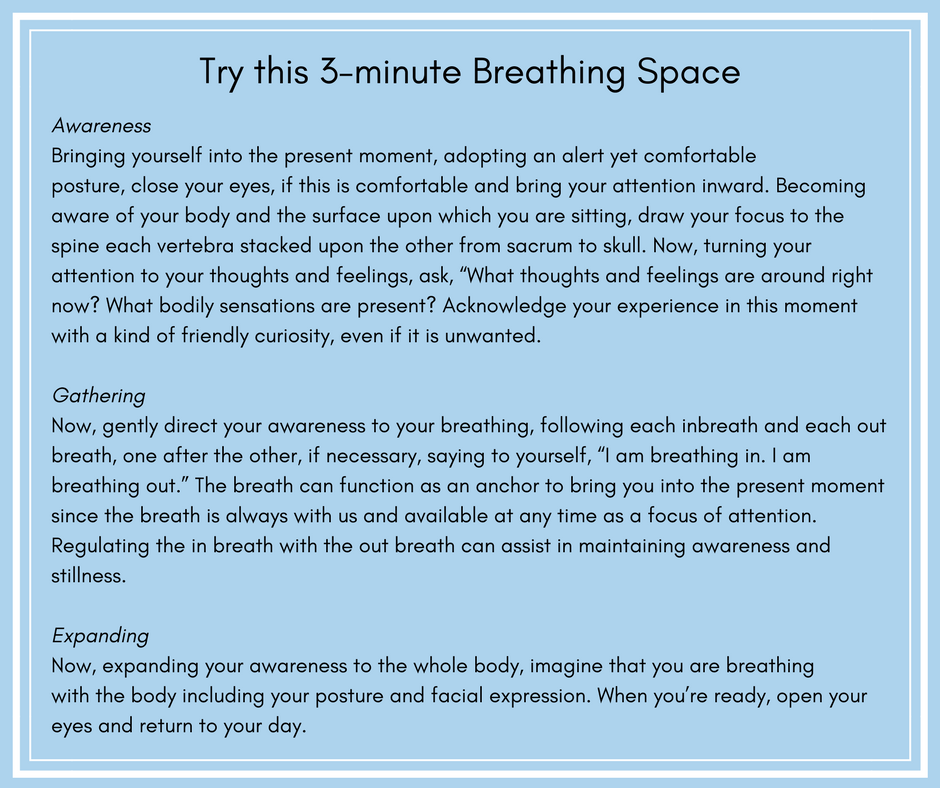

One way to begin to hone your attention is with “micro-practices” of mindfulness, such as by taking a 3-minute breathing space. This short, yet powerful practice offers a quick way to bring our minds purposefully online and strengthen the attention muscle-sort of like doing a mental push up. Set your timer for 3 minutes if that helps.

Mindfulness helps cultivate focus, which creates emotional ease and deeper relationships.

The ability to notice where our attention is going, for example, that to recognize we are getting anxious, and to take steps to renew our focus rests on self-awareness. Self-awareness is a key domain of emotional intelligence. Such meta-cognition lets us keep our mind in the state best suited for the task at hand. Of the many ways of paying attention, two are especially important for self-awareness:

- Selective attention lets us focus on one target and ignore everything else.

- Open attention lets us take in information widely – in the world around us and the world within us – and pick up subtle cues we otherwise miss.

Why is this important? It matters because being aware of ourselves, others, and the wider world goes offline when we are distracted. With the onslaught of stimulation from devices we need to learn to notice when we are distracted and intentionally remind ourselves to show up and focus. Here. Now.

The full extent of the emotional and financial toll distraction is taking is still not fully understood, but we are seeing early signs that it is devastatingly high. In fact, this month, two big Apple investors came out publicly stating that iPhones and children are a toxic combination. They are asking the company to be more socially responsible by helping parents limit cell phone use with technology settings they can easily activate, to turn phones off, or limit use.

The implication for leaders is clear. It is important to create a working environment that promotes the cultivation of focus.

Leaders can actively support their employees by creating structures and processes within the workplace that encourage mindful use of devices and mindful listening. For example, having people agree to not look at cell phones during meetings, leading a brief breathing space meditation at the beginning of a huddle, or setting guidelines on work emails afterhours and on weekends.

There is clearly great value for organizations who take the lead in helping their people cultivate these skills. Research found that among leaders with multiple strengths in Emotional Self-Awareness, 92% had teams with high energy and high performance. In sharp contrast, leaders low in Emotional Self-Awareness created negative climates 78% of the time. Great leaders create a positive emotional climate that encourages motivation and extra effort, and they’re the ones with good Emotional Self-Awareness.

References

Deloitte. 2017. 2017 Global Mobile Consumer Survey: U.S. edition. Survey, Deloitte.

Goleman, Daniel. 2013. Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence. NY: Harper.

Goleman, Daniel, and Richard Davidson. 2017. Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body. New York: Penguin: Avery.

Goleman, Daniel, Richard Davidson , Vanessa Druskat, Richard Boyatzis, and George Kohlrieser. 2017. Emotional Self-Awareness: A Primer. Northampton: Key Step Media.

Recommended Reading:

Daniel Goleman’s CD Cultivating Focus: Techniques for Excellence offers a series of guided exercises to help listeners hone their concentration, stay calm and better manage emotions.

The Triple Focus: A New Approach to Education provides educators with a solid rationale for incorporating focus-related skill sets in the classroom to help students navigate a fast-paced world of increasing distraction, and to better understand the interconnections between people, ideas, and the planet.

Our new series of primers focuses on the 12 Emotional and Social Intelligence Leadership Competencies, including Emotional Self-Awareness, Adaptability, Influence, Teamwork, and Inspirational Leadership.

The primers are written by Daniel Goleman and Richard Boyatzis, co-creators of the Emotional and Social Intelligence Leadership Competency Model, along with a range of colleagues, thought-leaders, researchers, and leaders with expertise in the various competencies – including the author of this article, Ann Flanagan Petry. See the full list of primers by topic, or get the complete collection!