It’s January, and you have a new set of weights which will finally keep you on track for a six-pack by this time next year. January is named after the Roman God Janus, god of transitions, beginnings, and endings, who is typically depicted with two faces. One looks to the past, one to the future. The past was the unused gym pass; the future is the chiseled abs. Somewhere in the middle is the hard work, the app you downloaded, and the kettlebell.

Regardless of whether your resolution is physical fitness or healthier relationships, the first day of the year is a universally accepted signal to stop living in the past and to break useless habits. It serves as a permission slip to be more present, take more chances, and live our best lives in the new year.

But how many of us actually do?

According to the U.S. News, 80% of people who set a resolution on January 1 break it by the second week of February. In other words, within six weeks of a well-intentioned change, we question, hesitate, and revert back to what is comfortable and known, even if it doesn’t work for us. Like Janus, our two faces constantly look backwards and forwards, but never focus on the present moment.

While there are wonderfully useful tips for how to stick to New Year’s resolutions–keep it simple, be specific, tell a friend–our brains tend to revert into our default mode in which we ruminate and dwell on what we coulda, shoulda, woulda. Or we worry about the future such that we forget to live in the moment. So instead of a quick, 10-minute set with our shiny new weights, we feel remorse at the third brownie we ate or worry about how to carve out time to do sit-ups for the next thirty.

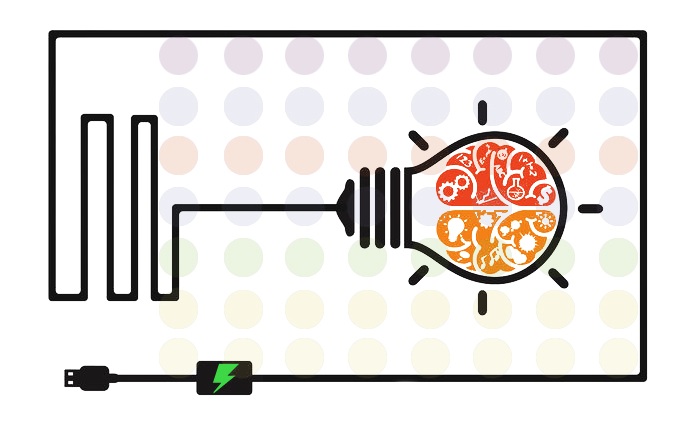

The term “default mode” was first used by Marcus Raichle to describe our brain when it is “resting.” However, studies suggest that our brain isn’t just idling when “resting.” For many of us, our brains default to self-referential thinking (thinking about ourselves), rumination, or preoccupation. We want to go the gym, but our brain’s default system may override its good intentions with fears: What if other people laugh at me; what if this is a waste of energy; what if I don’t have time? To motivate ourselves to put in the hard work, we must shift our mindsets. We need to rejigger our brain’s default mode to one from which we can learn from the past without grasping, be mindful of what may come without anxiety, and live in the uncertainty of every day without avoidance.

Working towards a six-pack is not simply a physical exercise, but also a mental one.

Our brains play a large part in how successfully we will achieve a declared goal–or any habit change. One key domain of Emotional Intelligence that is essential to shifting mindsets and habits is Self-Management, our ability to balance our emotions to make progress towards our goals.

The first Self-Management competency is Emotional Self-Control, or Emotional Balance, the “ability to manage disturbing emotions and remain effective, even in stressful situations,” according to Daniel Goleman. Change is scary, no matter how small it might be. Something as seemingly innocuous as, say, deciding to eat more vegetables, may uncover a deeper emotion or underlying issue. Perhaps eating more vegetables brings back unpleasant memories of a parent forcing you to eat something you didn’t want, and that memory evokes a sense that you are losing your agency to say, “no.” With Emotional Self-Control, we don’t ignore our emotions, rather, we don’t let them hold us hostage. When obstacles arise between us and our goal, we become less susceptible to the whims of our impulsivity and strong emotions.

Second, Adaptability allows us to see change as positive. Let’s say you want to end an unhealthy relationship. It can be scary to let that connection go, no matter how little benefit the relationship offers you or the other person. There is comfort in the known, albeit the dysfunctional known. To move towards the unknown is a transition, and whenever we transition from what was to what will be, we experience change. When we become more adaptable to the uncertainties of life–including the ultimate outcome of our desired goal–we can effectively respond to challenges and transform fear of loss into possibilities for development.

Third, Achievement Orientation is our capacity to meet or exceed a standard of excellence and continually improve. Without this competency, we wouldn’t have the same motivation to effect change and persist when we encounter roadblocks. Strengthening this competency allows us not only to better manage ourselves, but also the context around us so that we can adjust and adapt accordingly to meet our desired goals.

Lastly, the Positive Outlook competency isn’t just about hoping for the best or putting on a happy face. It is an inclination towards the positive. It’s not just an attitude; our brains betray whether we have a tendency towards a Positive Outlook. Neuroscientist Richard Davidson found that people with frequent activation in the left prefrontal cortex tend to be more positive in their emotional outlook. They also may get frustrated when something gets in the way of their goals–and that frustration turns into motivation. On the other hand, those with more activation in the right prefrontal cortex are more likely to give up when the going gets tough.

We can build our Positive Outlook by increasing our “stickability” when obstacles get in our way, and by finding goals that give us meaning and purpose. As Daniel Goleman notes, when we do so, our left prefrontal cortex lights up like a Christmas tree. It is what moves, or motivates, us to keep working towards that goal.

Building our Emotional Intelligence in these competencies helps us become more aware of our default explanatory style about how the world works. Martin Seligman, known as the “father of Positive Psychology,” posed that humans generally have two default explanatory beliefs about the way the world works and their own agency. The first is a pessimistic explanatory style whereby we tend think that our situations are set in stone and that what is wrong will always be wrong. The second is an optimistic explanatory style whereby we think that the opposite.

When it comes to habit formation, either style can be inhibiting if not managed appropriately. The former may be a Debbie Downer who gives up prematurely, and the latter a Polly Anna who ignores reality. While practical realism can prove beneficial, studies suggest that people more disposed to an optimistic explanatory style remain less likely to give up when the going gets tough. In other words, seeing the world with only rose-colored lenses obscures what is really in front of you, and may lead you to make more rash or impulsive decisions. But when we face reality as it is, yet view it with a sense of hope and positivity, we can better recognize how to make the most of whatever challenges life presents.

Want that six-pack by next Christmas? Consider supplementing your new weights with a dose of Self-Management and its four competencies for an inside-out approach.