“Don’t worry, be happy” is such a cliché that many people roll their eyes when they hear something about the importance of thinking positively.

Barbara Fredrickson isn’t one of those people.

For over twenty years, Dr. Fredrickson has studied how positive emotions improve physical and emotional well-being, as well as performance at work. More Than Sound author Daniel Goleman cites Fredrickson in his introduction to Positive Outlook: A Primer, the fifth in the series focused on the twelve Emotional Intelligence Competencies. Research conducted by Fredrickson and her colleagues shows that people who experience and express positive emotions more frequently are more resilient, more resourceful, more socially connected, and more likely to function at optimal levels.

One of Fredrickson’s key contributions is her “broaden-and-build” theory which presents an understanding of the evolutionary value of positivity. Positive emotions widen a person’s outlook in small ways that, over time, reshape who they are. In a threatening situation (or one we perceive as threatening), our view of options literally narrow as we choose one response and react quickly. In situations that evoke positive emotions such as joy, interest, contentment, or love, we can see a wider range of possible responses. Fredrickson describes this effect:

“…positive emotions broaden peoples’ momentary thought-action repertoires, widening the array of the thoughts and actions that come to mind. Joy, for instance, creates the urge to play, push the limits and be creative; urges evident not only in social and physical behavior, but also in intellectual and artistic behavior. Interest, a phenomenologically distinct positive emotion, creates the urge to explore, take in new information and experiences, and expand the self in the process…. These various thought-action tendencies””to play, to explore, or to savor and integrate””each represents ways that positive emotions broaden habitual modes of thinking or acting.”

This “broaden” part of the theory has been proven in empirical research conducted by many laboratories.

The “build” aspect looks at the cumulative impact of that “broader” thinking. Seeing a broader perspective allows us to discover and build personal resources. Fredrickson says it is a:

“…recipe for discovery: discovery of new knowledge, new alliances, and new skills. In short, broadened awareness led to the accrual of new resources that might later make the difference between surviving or succumbing to various threats. Resources built through positive emotions also increased the odds that our ancestors would experience subsequent positive emotions, with their attendant broaden-and-build benefits, thus creating an upward spiral toward improved odds for survival, health, and fulfillment. In sum, the broaden-and-build theory states that positive emotions have been useful and preserved over human evolution because having recurrent, yet unbidden, moments of expanded awareness proved useful for developing resources for survival. Little by little, micro-moments of positive emotional experience, although fleeting, reshape who people are by setting them on trajectories of growth and building their enduring resources for survival.”

Positive Outlook and Today’s Leadership

Fredrickson’s concept of “broaden-and-build” doesn’t relate just to long-ago ancestors surviving, it provides an important lesson for leaders today. Leaders and the people with whom they work experience the same broadening and building through positive emotions. In a work setting, people who regularly feel positive emotions are more able to think creatively, consider novel solutions to problems, and take advantage of opportunities that might not be immediately obvious.

Leaders who are strong in the Positive Outlook Competency see others positively and help their colleagues recognize the positive in what others might consider a setback. By continually evoking positive emotions in the people around them, leaders help build the capacity of their teams to be successful in their work.

Recommended Reading:

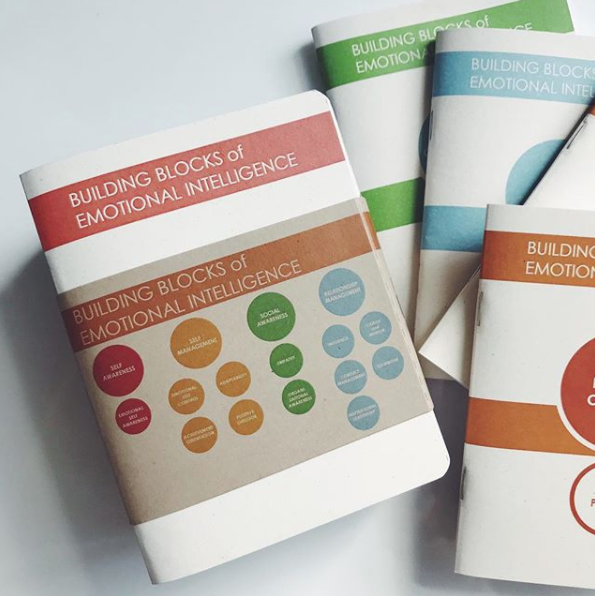

Our new primer series is written by Daniel Goleman and fellow thought leaders in the field of Emotional Intelligence and research. The following are available now:

Our new primer series is written by Daniel Goleman and fellow thought leaders in the field of Emotional Intelligence and research. The following are available now:

Emotional Self-Awareness, Emotional Self-Control, Adaptability, Achievement Orientation, and Positive Outlook.

For more in-depth insights, see the Crucial Competence video series.

References:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124072367000012

http://www.unc.edu/peplab/publications/Fredrickson%202013%20Updated%20Thinking.pdf