S1E8 Constructive Anger

Can anger be a constructive emotion? According to Daniel Goelman, “YES” —especially when it comes to creating change for the better. Today’s guests, Lama Rod Owens (Author and Activist), Shayna Renee Hammond and Lauryn Henley (Racial Justice Coaches and Advocates, and Asli Ali (Student and Poet), each share how anger fuels them to take action on issues that matter.

Our Guests

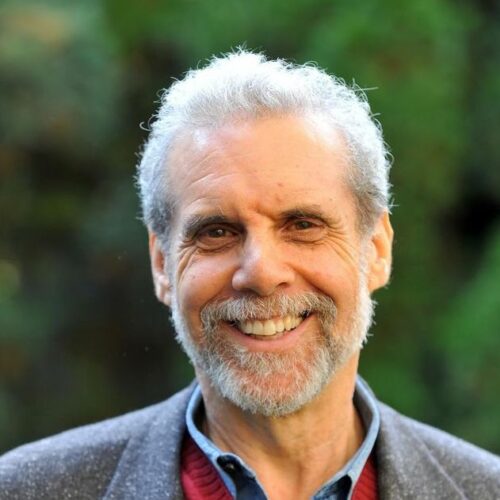

Lama Rod Owens

Lama Rod Owens is a Buddhist minister, author, activist, yoga instructor and authorized Lama, or Buddhist teacher, in the Kagyu School of Tibetan Buddhism and is considered one of the leaders of his generation of Buddhist teachers. He holds a Master of Divinity degree in Buddhist Studies from Harvard Divinity School and is a co-author of Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love and Liberation.

Owens is the co-founder of Bhumisparsha, a Buddhist tantric practice and study community. Has been published in Buddhadharma, Lion’s Roar, Tricycle and The Harvard Divinity Bulletin, and offers talks, retreats and workshops in more than seven countries. Lama Rod’s new book, Love & Rage: The Path to Liberation Through Anger came out to critical acclaim in June 2020, and was cited as one of the books of our times, at period of pandemic and uprisings for social justice held the worlds attention.

Shayna Renee Hammond

Shayna Renee Hammond is a leadership and life coach who has coached and developed thousands of school and executive leaders within the education and non-profit sectors for nearly 20 years. She is the Founder and CEO of Lead For Liberation (formerly known as Teach To Lead), a leadership development organization dedicated to guiding organizations, school districts, foundations, and communities to demystify and operationalize liberatory cultures. Through Lead For Liberation’s support, schools and organizations across America have experienced unprecedented school growth and achievement outcomes, inclusive school and organizational cultures, and strengthened teacher, principal, and executive leader effectiveness and retention.

Inspired by the success of Lead For Liberation in the education and non-profit sectors and her calling to raise global consciousness, Shayna recently founded Shayna Renee, a coaching practice dedicated to creating spaces, methods, and conditions for Black womxn in leadership to thrive. In this capacity, Shayna coaches individual and groups of Black womxn executive leaders and entrepreneurs from around the globe in a spiritually-inspired and research-based coaching methodology created by and for Black womxn. Shayna Renee’s methodologies and spaces inspire and equip Black women in leadership to rejuvenate their minds, bodies, and spirits so that they can lead more authentically, effectively, and sustainably.

Shayna extends the love and power she brings to her work beyond her role as an entrepreneur by serving as a faculty member and meta-coach at Goleman EI’s Emotional Intelligence Coaching Certification Program and serving as a spiritual life coach and facilitator for Harriet’s Apothecary–a healer’s collective led by Black cis women, queer, and trans healers in partnership with ancestors and the earth itself. She also serves as a Board Trustee for a few organizations including Livelihood Trust, a community economic development organization as well as St. Patrick’s Episcopal Day School in Washington, DC.

Prior to founding Lead For Liberation and Shayna Renee, Shayna led the national development of teacher leaders at KIPP Foundation, supported principals within the Baltimore City School System, led the highest-performing middle school in Baltimore, Maryland, and was an award-winning teacher.

Shayna earned a Bachelor’s degree in Kinesiology with minors in Business and English from James Madison University, a Master’s degree in the Art of Teaching from Johns Hopkins University, and a Master’s of Education degree focusing on Administration and Supervision from National-Louis University. She completed the Certificate in Leadership Coaching Program at Georgetown University and is also a part-time faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education’s PENN Literacy Network.

When Shayna isn’t coaching, facilitating, or leading, she’s enjoying quality time with her two children, Judah and Joelle, learning a new sport, showing up for her Tribe, or exploring a new venue for spiritual growth and renewal.

Asli Ali

Asli Ali lives as a proud resident of Western Massachusetts with her parents and two younger brothers. She is a first generation American; her family is originally from Somaliland, East Africa. Tracing her creative process back to her lineage, Asli notes that both of her grandmothers were known to be profound storytellers and singers within their respective communities. Drawing from this energy, Asli finds herself immersed in the stories behind movies, books, shows, personal accounts, and music that inspire her to write her own.

Asli Ali is an undergraduate student at Smith College pursuing her degree in environmental science and policy with a minor in Arabic. She resonates with the environmental discourse in her courses and aspires to spread awareness in her surrounding communities. She hopes to continue to learn and speak up on environmental issues in the future, and further develop her voice.

A self-identified empath, Asli enjoys engaging in varied conversations with others, and incorporates her interpersonal skills in her variety of telecommunication and mentoring positions. In her free-time, she enjoys daydreaming, reading, having Netflix parties, and spending quality time with her many loved ones.

Lauryn Henley

Lauryn Henley is the Program Director at Lead For Liberation (L4L), where she is on purpose supporting the liberation of all people through strategic partnerships and as the Lead Facilitator of The Conscious Racist program.

For the last 18 years, Lauryn Henley has worked as a leader, speaker, facilitator and consciousness coach whose purpose is to support individuals, families, communities and organizations to liberate themselves, thrive and experience transformative relationships.

Lauryn is deeply committed to ending systemic racism and views this as her life’s work since she was 19. In 2003, she graduated from the University of Florida with a Bachelor’s in Psychology focusing on race and multicultural studies. Specifically, she studied the role that white people play in perpetuating racial injustice. At that time, Lauryn was committed to racial equality through educational transformation and joined Teach for America in 2003.

For thirteen years, Lauryn worked on the west side of Chicago as a teacher, and school leader at KIPP: Ascend Middle School. During this time, she was also coaching and consulting around diversity, achievement and inclusion at 6 Teach for America Summer Institutes.

Lauryn’s journey as a school leader led her to the conclusion that in order to disrupt the system and change behavior she needed to start at the level of consciousness. As a result, she participated in four Conscious Leadership forums as well as began facilitating white affinity spaces and consciousness classes at Bodhi Spiritual Center in Chicago. In 2019, Lauryn was certified as a 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership Coach and left her 16-year education career to work as a leader, speaker, consultant, and coach who partners with individuals and organizations to support the emergence of more conscious cultures.

Lauryn received a Masters in Curriculum Planning and Design from National Louis University, earned a National Board Certification in Literacy and completed the KIPP School Leadership Training Institute at New York University, in 2011. In 2009, Lauryn was awarded Teacher of the Year for Chicago Charter Schools and in 2011 was a finalist for the Teach for America Distinguished Leader Award.

Lauryn is also an inspiring public speaker. She has been invited to speak at the National Charter School Conference in Minneapolis, and as a keynote speaker for Teach for America’s Induction Ceremony, at North Park University, Columbia College, and Indiana University-Purdue on Leadership, Consciousness, and Education. She also co-hosts a weekly podcast called The Healing Collective podcast that discusses the paradox of collective healing.

Lauryn is a proud mother to her fourteen year old son, Taylen and loves communing with nature, creating sacred rituals as a celebrant and forging deep, meaningful relationships with the people closest to her.

Resources

The following resources were referenced in today’s episode:

- A Force For Good: The Dalai Lama’s Vision for Our World written by Daniel Goleman

- Love & Rage: The Path to Liberation Through Anger by Lama Rod Owens

- Intentionally Placed Pollution by Asli Ali (see full poem in transcript below)

- Support our podcast by becoming a monthly Patron.

Subscribe to the podcast:

Subscribe now and sign up for our newsletter to get notified as new episodes are released.

Have feedback? We want to hear it! Submit a Voicemail.

If you enjoyed today’s episode, please rate our show and submit a review. It helps us spread the word about the show.

Episode Credits:

This show is brought to you by our co-hosts Daniel Goleman, and Hanuman Goleman and is sponsored by Key Step Media, your source for personal and professional development materials focused on mindfulness leadership and emotional intelligence.

- Special thanks to Rowan, whose voices you heard at the top of the show.

- This episode was written and produced by Elizabeth Solomon and Gabriela Acosta.

- Episode art and production support by Bryant Johnson.

- Music includes Aerial; Industrial Zone; and Fairground by Bio Unit. Theme music by Amber Ojeda.

Please note that following this episode, First Person Plural: EI & Beyond will be switching to a summer schedule in which we will be publishing single-interview episodes, to air on the 3rd week of each month through the Fall.

Transcript

Mom 0:00

Have you ever felt mad about something you thought was unfair? And what happened?

Rowen 0:06

So we’re playing Foursquare recess school. My friend, he was making unfair rules about other kids to not do the rules that other kids were doing. And that kind of felt unfair, because they could literally just only drop the ball because that’s what he said. And all of us could do like cherry bombs, but only he could do like dropping the ball. So I would be really unfair.

Mom 0:36

And how did it make you feel inside?

Rowen 0:40

kind of mad sad for like the person who would only do like dropping a ball? Right? Yeah.

Mom 0:47

What happened? Were other kids, mad?

Rowen 0:50

Yeah. Most of the people that were playing Foursquare, were angry.

Mom 0:55

So what did you do?

Rowen 0:57

I just went to the different Foursquare.

Mom 1:00

Awesome.Okay, thank you.

Rowen 1:03

You’re welcome.

Daniel Goleman 1:17

I’m Daniel Goleman.

Hanuman Goleman 1:18

And I’m Hanuman Goleman.

Daniel Goleman 1:20

You’re listening to first person plural, emotional intelligence and beyond. Today, we’re talking about constructive anger. Reacting negatively to injustice or suffering can motivate us to work with others to make the world a better place. Just as empathy has its downsides. negative emotions, like anger can have upsides. staying cool in a crisis might bring some benefits. But sometimes we must let ourselves get heated. In order to make positive change. In emotional intelligence, we often talk about emotional balance, which is the ability to keep your disruptive emotions and impulses in check to maintain your effectiveness under stressful or even hostile conditions. It means that you recognize disruptive emotions, emotions that get in the way, like high anxiety, intense fear or quick anger. And you find ways to manage your emotions and impulses. But there’s a usefulness and feeling strong emotions such as anger, when we experience injustice, anger can give you the energy to stay focused and motivated to address a particular goal. When the Dalai Lama turned 80, I was honored to be asked to write a book for him that articulate his vision for the world. And one thing that startled me was finding out that he’s really at heart as social activist, he gets really incensed about injustice, social injustice, about us, and then biases, about the widening gap between rich and poor. And he sees a role for anger. And that really surprised me, because in Buddhism, generally anger is often seen as something you want to suppress. But he didn’t say that at all. He said, you know, anger can be constructive. If it’s well guided, you can use the focus that anger gives you you can use the energy that it gives you, you can use the persistence, that anger gives you just put aside the hatred, moral outrage can drive positive action, he said, and he he told me once about being talking to a group of social workers, who were going on strike, to protest how a very poor people were being treated in a city in India. And he said, If I weren’t the Dalai Lama, I’d be right there with you on the picket line. He’s an activist and I, however, I think that it’s useful to experience anger, and then take the gift of anger on with you in how you react to what’s making you angry. And that’s what he calls constructive anger, where you transmute the anger into energy into focus into clarity into purpose, and pursue a goal, which is effective in writing the wrong that made you so angry in the first place.

Hanuman Goleman 4:32

I love that you were talking about the clarity that anger offers, because clarity is a big piece of anger for me if I have the presence of mind to listen to it in the right way, because anger makes things very simple, right? It’s things often become either black or white. It’s either this or that and especially when we feel we’ve been wronged, which I guess anger often is. It’s not that you can’t get angry because anger is just information. It’s just if we can listen to it, if we can hear it, it’s telling us how what we care about and what’s important to us, and maybe that our needs aren’t being met. But it. So I wonder, Dan, if you could talk about from an emotional intelligence perspective, if you could break down the emotional process of feeling something, and then using that feeling as motivation, you know,

Daniel Goleman 5:26

Emotions are the brains way of making us pay attention have an instant way to react. And in early human history and evolution, that was a survival strategy. And it worked. Apparently, at least for our ancestors, we don’t know about the ones that didn’t serve. But anyway, we have this hair trigger in our brain, which makes us angry and instant, all emotions come to us, unbidden. We don’t ask for them. Usually, they just all of a sudden, we find we’re sad, we’re anxious or angry. Once you have the feeling once, the question is, what do you do, that’s the choice point, you didn’t choose to be angry. But now you find you’re angry. And you can either act on it impulsively, or not, in fact, one definition of maturity is widening the gap between your initial emotion and how you react, that emotional impulse and the reaction and with anger. I think that not acting on the first impulse is a good idea. I was recently attacked in an article, a very high profile venue. And it made me really mad, because it wasn’t justified as far as I thought, as far as I could see. So I took the anger, and there was a mix, there were other feelings, anxiety, shame, fear, you know, this whole mix of unpleasant feeling. And I just sat with it. I’m a meditator. And I let it be I tried to experience all of it and the thoughts, you know, like I thought, to defend myself, I’ve got a counter attack. Those were the impulses that came with the feelings. I didn’t act on any of it. And in fact, the longer I sat with the feelings of the thoughts, the less powerful they became. And I came out of that with interesting clarity about what to do, which was to take a good look at what I’ve written about emotional intelligence, and what people are doing with it, and tried to separate, what’s good, what’s bad, what’s a good use, what’s a misuse, what’s really ugly, what’s admirable. In other words, sort out the entire thing, and that was stimulated by what I took to be a very unfair attack on me, and the concept. But my final response came with clarity, with energy, with motivation with focus.

Hanuman Goleman 8:02

That’s beautiful. It’s a beautiful example of feeling very strong feelings, and taking the time to experience them, and, and really allow them to unfold inside of you without unfolding outside of you. And at the same time, I feel like, it’s really important to recognize that it’s really rare that we have the capacity, first of all the practice to know that that’s a possibility. And second, the conditions to be able to take the time to reflect in our response, or the habit of doing that. And I think in those conditions, there’s a lot of privilege that it’s important for us to just recognize because so many of the people in the world don’t have the privilege conditions to take a moment with anger.

Daniel Goleman 9:15

I’m Daniel Goleman. And I’m here with Lama rod Owens, who’s a Buddhist minister, author, activist, yoga instructor and authorized Lama or Buddhist teacher in the congu School of Tibetan Buddhism. His book, Love and rage, the path to liberation through anger came out to critical acclaim last year. So I think it would be helpful for our listeners if you explain who you are your various identities.

Lama Rod Owens 9:47

Absolutely, yes. Well, I identify as black and queer, just gender. I’m a southerner. I’m also fat identified, mixed class. very radical leaning, radical minded. And, yeah. And I love having a good time, but at the same time also love serious work. So that creates sometimes extremism. And I do, but I think it’s also my experience of myself has been being very, like very live and in color. That makes sense. Like, I am definitely showing up very strongly in the world, even when I think that not showing up, I’ve been told that I am showing up, you know, and so all those identity locations are so important for me. You know, and, of course, course I’ve mentioned that I’m also a Dharma teacher, Buddhist teacher. And that makes it even more interesting, as well.

Daniel Goleman 11:16

And then I think it’s the pivot point of your book. But we’ll get to that. Yep. So what are the things I like is right at the beginning, you said, you know, this is not a bypass. We’re gonna dive right into it. And why do you think that’s so important?

Lama Rod Owens 11:32

Yeah, I think so many people are used to, kind of, kind of stepping around anger in general, he really just any strong emotion, but definitely anger. You know, and, and I want it to really say very clearly that we’re going to go into the anger. And we’re going to get into the roots of anger, which, you know, again, which we perpetually avoid, because many people really don’t believe they have the capacity to actually be in relationship to the anger, they think they have to kind of turn directions when they see the anger and do something else.

Daniel Goleman 12:16

Kind of just protect ourselves.

Lama Rod Owens 12:18

Yeah, but yeah, protect yourself. Right? No. Yep.

Daniel Goleman 12:21

So but let’s get right into it. You talked about anger and hurt and wounded. Yeah. Explain. Can you unpack that?

Lama Rod Owens 12:29

Yeah, absolutely. You know, I just for me, it’s, you know, often see anger as a secondary emotion, the primary emotion being the woundedness, the hurt, like, I get hurt, like, something happens, and I still hurt. And I want to take care of myself. But I don’t know how to do that. And so there’s a tension that arises, the tension is what feeds into this experience of anger. But I believe that what people are really trying to say, when they say, I’m angry, I think they’re actually trying to say, I’m hurt, and don’t know how to do that. And so the anger and the energy of anger is much more accessible than the hurts the anger, you know, anger, this energy is really strong, it’s dynamic, you know, but the energy of woundedness is very, it can feel depleting, it can feel depressive. Right. And we don’t want to sink into that. You know, but we want to rise in the anger.

Daniel Goleman 13:31

So, you’ve also talked about having been conditioned to see your anger is dangerous. Yes. bearing.

Lama Rod Owens 13:40

Yeah. Yeah. Well, you know, for me, growing up as a black male in the south, I learned very early and saw very clearly that it was quite dangerous for me to express anger. And I saw what the discipline was, I saw what the retaliation looked like, you know, even in school, right? Like, I couldn’t be angry because that was always read into as being me being, you know, hard headed, are having behavior issues, when in fact, I was just angry, like any other kid is angry, you know, but as I got older, actually, I began to, to understand it, like it was even more dangerous. Like I didn’t, I didn’t have the space to be angry.

Daniel Goleman 14:26

You talk about how anger kind of suppressed to turn inward can become depression. Yeah. And you also make it really clear about needing a relationship with the hurt under there. Yeah. Why is that?

Lama Rod Owens 14:42

How is Yeah, well, it because that’s the truth of things like I am experiencing hurt. I need to be in relationship to the hurt in order to figure out how to take care of that hurts. And if I don’t take care of the hurt, I won’t ever be in a really effective spacious relationship with the energy of anger.

Daniel Goleman 15:03

So here’s here’s something that I found a little confusing, maybe you can help me. You he talked about getting in touch with your anger and letting yourself feel the rage. And also, you have this wonderful Viktor Frankl quote right at the heart of your book about expanding the space between whatever triggers the feeling, and then what you do about it. How can you on the one hand, really experience the anger and regret the other hand, not let it take you over and do something that might harm you or someone else?

Lama Rod Owens 15:38

Well, I think the key practice here is experience I want to experience not react, you know, and and my meditation practice, when I’m training to do is to actually disrupt the ways in which I habitually react to everything that arises in my mind. And doing so I can turn it attention to the space that’s already naturally in my mind. Right? So then I begin to understand that like, actually, maybe it’s almost impossible for anger, to overwhelm me, when in fact, over years of practice, I can realize that my mind and space in my mind is quite boundless.

Daniel Goleman 16:20

But one of the things that you talk about really powerfully is systemic violence, feeling marginalized, feeling victimized? What does that look like, from your point of,

Lama Rod Owens 16:30

yeah, it’s really this deep experience, or living in a social context where I feel, that can’t really be myself. Right, you know, that I’m moved to the world, and there are all of these, these actually cultural rituals that have been and acted, you know, to prevent me from experiencing freedom, like what, you know, so like, one of the these cultural rituals, you know, like, being in a body, where the Supreme Court has to litigate my right to do something that other people get a right to do, like, I don’t know, get married, you know, are to be able to vote without being discriminated against or to be able to have a job, it’s a fairly be able to say that maybe I’m being discriminated against because of an aspect of my identity.

Daniel Goleman 17:25

So these are all systemic hurts, yes. That understandably, create anger.

Lama Rod Owens 17:30

Yeah, well, and then then, then is also the trauma that is also translocal traumas that are passed from generation to generation, I began to study trans historical trauma, from the perspective of Holocaust survivors. So so I have friends whose family survived the work camps and death camps, nope, mostly work camps. And that’s where I began to understand, oh, there’s this field of study that talks about historical traumas and how they get rooted within communities and then passed from generation to generation. So when I looked into my heritage, I, you know, I am descended from mostly, you know, African, you know, and particularly African enslaved people, and I do have some indigenous ancestry as well. But the Middle Passage, writes this experience of Africans being packed onto ships, and then sells to different countries, you know, the Caribbean, the United States and so forth, different countries, that experience created this, this trauma, this deep hurt the steep one, it’s one of this which was both both mental and physical, you know, and I would also argue spiritual as well. And then coming into whatever context they were being brought into being being put into systems of slavery, chattel slavery, slavery, to be precise, and then years of racism, you know, and so forth, has created trauma, you know, that has been passed from generation to generation, and perpetuated by systems of racism. And so, you know, I, you can look at, you know, the the research around epigenetics, for instance, and to show how one’s DNA has, can be shaped by trauma.

Daniel Goleman 19:24

In that, I mean, epigenetic research I’m familiar with shows that if a, one generation is neglected, or abused, that that actually changes what genes are passed on, and what’s activated and what’s not, which is very powerful because it gets to the level of the body, which you emphasize. you emphasize how important it is to feel this in your own body. Right. Can you say something about that?

Lama Rod Owens 19:54

Yeah, absolutely. I just for me, from you know, from my perspective Particularly in Buddhism, I, the body is important in terms of experiencing liberation, you know, because I have to have a complete awareness of everything, my whole experience. But when I think about the body in the contemporary context of, you know, maybe a more secular context, what I understand is that, you know, so many of us are disembodied, you know that we actually have no connection, no experience of the body, you know, I often say that, we’re such a head, mind oriented culture, because the mind can can move in the past, it can move in the present, you know, but the body is always in the presence, you know, the mind can move into the future, as well. The body is always here in the present. So when we are actually bringing awareness back to the body, we’re actually going to have to slow down, right, but we’re also going to have to begin to experience the ways in which the body has absorbed pain, and it carries pain and carries hurts, right. And then, and that’s what I would call trauma, you know, and we won’t experience the kinds of a freedom or happiness or joy until we do the work of tending to the trauma, physical body.

Daniel Goleman 21:18

And part of that is just tuning into your own experience of what that’s like. Yeah,

Lama Rod Owens 21:24

yeah. And being as careful as possible. Absolutely. So,

Daniel Goleman 21:28

but also, I was struck that you seem to be working at multiple levels, one of them is in the body. And then the other is the emotion and then another, it’s society, you’re a social activist, you said, right. And how has your social activism helped you? or What does it mean for you?

Lama Rod Owens 21:48

Right, you know, I, I’ve been involved in activism. I really just service in general, since my early teens, and I just, it was just important for me, to, to be of benefit, somehow, right. And then, of course, being in this body being black and queer, you know, particularly, I was very sensitive to the ways in which, yeah, there are these, these, how society was set up, you know, to create limitations, right. And I wanted to do something about that. Absolutely. I wanted to be happy, right. In order for me to be happy, I had to add to do what I could to create freedom for myself. And for those, like me, for me, it’s been about trying to create and secure the space for me to be my complete self, and that has taken action on has taken a kind of awareness, I’ve had to question why I’m not able to be my complete self, and then taking another step and saying, Okay, what am I going to do about this?

Daniel Goleman 23:00

So you earlier mentioned that you have also, not just black ancestry, but Native American ancestry? How does indigenous spiritual practice inform your work around social justice?

Lama Rod Owens 23:12

Yeah, I mean, I, in connecting to my indigenous ancestors has been a newer kind of practice. But even so, my practice has really been extremely impacted by the ways in which indigenous practice has reconnected me to the earth, to the elements connected me to different ways of understanding community, you know, and to when I talk about indigeneity, I’m also talking about pre colonial ways. You know, like, what does that look like? You know, I’m really also fortunate to be in a relationship with indigenous, indigenous native folks, as well. And so building practices, right, which, for me, comes at this intersection between Buddhism and indigenous practice, you know, what, which has been a part of is so hard for me to articulate but another part of it is just this feeling of, again, becoming more myself. Right? Like, who am I, if not defined by a system, you know, of violence and prejudice, like, Who am I outside of that, and that’s what’s happening. I’m figuring out who I am outside of those systems.

Daniel Goleman 24:40

What are the things that I was struck by in your book, which is so wonderful, and I recommend it for everyone. was how you viewed Martin Luther King. Yeah. Because here’s a guy who many people see as a very effective activists working for social justice. And yet you saw some limits, I think, and how we did. Did you explain that?

Lama Rod Owens 25:04

Well, while he was quite effective, he you know, and that’s, I think that’s an important thing. He was extremely effective. I think he was extremely gifted. But I think that we tend to over emphasize this non violence and kind of bypass the importance of violence within his work, right, you know, the civil rights movement was spurred was it was galvanized primarily, because people were able to turn on a TV or pick up the paper and see police or other people beating black people, and I can’t even watch those images anymore. You know. And so when I began to feel that I said, Oh, violence is playing a part. And Dr. King’s nonviolent work, nonviolent resistance,

Daniel Goleman 25:58

you also talk about the role of violence, you talk about a jotika tale. The Buddha, himself became violent, but to protect other people. Yes. So what are the boundaries? You know, put around violence?

Lama Rod Owens 26:11

Yeah, absolutely. And this is really interesting, because this is going to be part of my next book. Oh, you know, looking at violence? Because this has been the number one question this year for me and for a lot of folks who have been in dialogue with so the question that I’m working with is, like, how can I skillfully use violence to disrupt violence? You know, and how can I come from a place of actual authentic love? But I’m doing that. And so that’s the question I’m working with now.

Daniel Goleman 26:49

It raises a lot of questions like What do you really mean by violence?

Lama Rod Owens 26:52

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. Because I, I really think that we, we haven’t really, I mean, individually, personally, just folks in general, we don’t really know exactly what we’re getting at when we talk about violence. And what I’m trying to do right now is define that for myself. What is violence? Right? When have I been most violent? When do I choose violence? You know, and, of course, like, the basic distinction I’m making is that Yeah, there’s violence that I engage in to hurt other people as much as they hurt me. There’s violence that I choose to engage in, because I’m actually trying to protect

Daniel Goleman 27:38

and inland jotika tail. Yeah, the Buddha is protecting the person he’s violent toward from his own bad karma of violence. Let me ask you about something that the Dalai Lama talks about. He talks about a constructive anger. He says, take the focus of anger, take the energy of anger, the persistence of anger, put the hatred aside, and then act.

Lama Rod Owens 28:05

Yeah. Well, that’s, that’s tantric anger. And like, that’s, that’s 100, you know, because it’s like, let’s dissenter, the self

Daniel Goleman 28:14

anger and see what happens. One of the things that I was very touched by was your, your saying passing, the one of the things you hope to do or leave as a legacy is to lessen the burden of anger for future generations. And, you know, so it’s a question of your becoming an elder for new generation of black activism, queer activist, spiritual activists. So how do you feel about that? And what does that mean to you? Is this part of your purpose or mission?

Lama Rod Owens 28:51

Absolutely, absolutely. I am. I just, I am excited about eldership. You know, I’m excited about living the best life that I’ve been able to live and then providing support for those coming up, you know, behind me to do that work. I, I’ve been so deeply held and benefited by elders, and I still am. You know, and this just, this is part of the cycle, I think, for me is to step into eldership. You know, and, and just to point out to that being, you know, a queer and gay man, like, the elders, folks older than me, that generation of gay queer elders were mostly killed by the AIDS epidemic. Wow. It was also the epidemic. And so I didn’t really grow up with gay or queer milk ownership. And so this is a conversation that I have with others. queer male friends and my, we’re about the same age that like we find ourselves getting into eldership, like in our 40s, you know, because there’s, there’s no one else above us, right?

Daniel Goleman 30:13

Let’s talk about love, love and anger. And before we get there, why do you think a book called Love and rage resonated with so many people? I think that’s a pairing of those words. Yeah,

Lama Rod Owens 30:29

I think people found that really interesting and maybe paradoxical in a way. But those were the first two words that came to mind when I started thinking about this book.

Daniel Goleman 30:44

Well, it’s the idea that love can transform anger is really pivotal for you. Yeah. And the practices you offer seem to be a way to help people follow that path. I’m a foster student, myself. And I can recognize the visor on influence. But I see the how you’ve melded together many other streams, you’ve really woven together. Yes, different traditions in the path you put together, which is quite original. And do you find that people who come to with a lot of anger and rage for the reasons you’ve described are actually able to transform with these methods?

Lama Rod Owens 31:34

Yes, you know, but, you know, as I point out in the book, these methods aren’t that not instance, like this. These are insert result practice Exactly. This is, you know, diligence and efforts and long term practice, you know, but what I do find with folks coming into these practices for the first time is that they feel as if something’s working, they feel as if they have the hook in something. And that’s that motivates the practice quite a bit to continue.

Daniel Goleman 32:07

You’ve used a phrase that really struck me just as spaced mindfulness, yes. Because mindfulness is everywhere. It’s very faddish, the off days, and it’s very watered down, as I’m sure you recognize, very often. But that helps it go large go to scale. It’s not very deep, from a practitioners point of view. But just a space mindfulness. Wow, that’s a powerful hook, I think.

Lama Rod Owens 32:32

Yeah. And, and the work of the book, that’s just the beginning, maybe we can talk about what does a mindfulness look like, that’s really concerns, you know, with with how the world is with how people are not just focusing on me, but how I relate to the collective and relate to systems.

Daniel Goleman 32:52

And of course, this has been a big critique of mindfulness is there’s two main focused and ignore society. Yeah. So so you’re bringing the social concern into the practice,

Lama Rod Owens 33:03

right? You always have to do this work. And not there’s a line that we’re always toying, you know, because there’s always the tension between the Buddhists, you know, and the secular spaces, conspiracy theory that the Buddha is to try to take over all these spaces. And I say, like, we’re not that organized to do that. So don’t worry, don’t worry.

Daniel Goleman 33:33

You know, you also bring in other traditions yoga, yes, the Native American. And then you have this s, n, o, e, , l, l. see, it, name it, own it, experience it, let it go. Let it float. Can you walk us through that? Yeah. That’s a lot of work.

Lama Rod Owens 33:53

Yeah. And, you know, I think everyone has a different pronunciation of that. I, I just called it SNO-L. But people think it’s SNOW-EL,

Daniel Goleman 34:05

it’s like it’s Yeah.

Lama Rod Owens 34:07

So I just say what Call it whatever you want. Um, but yeah, i. So that methods came out of working with activists. Actually, at the very beginning of me, thinking about the book, I was working with a small group of activists, you know, meditation and issues of justice and meditation and collaboration. And that came out of our work together, you know? And yes, it’s very reminiscent of rain, which is recognize except investigate and not identify or nurture, depending on No one likes it, no, but activists, particularly activists of color, were like, well, we want more agency in this and so then That’s where the owner came from. So looking at the whole process, we see it, we name it, that’s very common, right? You know, we see that. And then owning it meant that, like, I needed to identify that this was happening in my experience, right? You know, because systematic oppression, oppression creates this, this experience that we don’t own anything. Like our body is knowledge our mind is a mass and that all this is dangerous in a way. You know, since we don’t own it, it’s we can’t trust it. So this opening is a way for us to step back into claiming our bodies claiming our minds. Even if we’re working with something really uncomfortable, it’s still happening in our experience, you know, and then we move into this kind of experiencing Okay, what does it feel like? Now, now that I’ve owned it, I can step into it now. And experience

Daniel Goleman 36:00

you know, so right there if I could just pause. This is really interesting to me, because I’m fascinated by shared blind spots. Yeah, there’s a blind spot about racism. Yeah, there’s a blind spot about anti gay. In prejudice and bias. There’s a blind spot. There’s a huge blind spot about how things read by a news every day or degrading the systems of sport life on the planet. Right. There’s another blind spot about economic the gap between rich and poor. Yeah, worldwide. These are all blind spots. So you’re saying go into it, name it. Own it is own it imply do something about it?

Lama Rod Owens 36:45

I think so. Yeah. Yeah, I would say that. Yeah. You know, and I think further incarnations of this practice, we’ll get into that, you know, as I’m working on other things, but But yeah, like, do something like where’s the doing? You know,

Daniel Goleman 37:04

maybe it’s your next book. But it seems to me that those are broad categories where naming is not allowed. You’re not? You don’t see what we don’t see. Right. Right. And if we don’t see it, we can’t name it. If we don’t name it, we can’t own it. or do anything about it. Yeah. Yeah. But that’s a kind of positive. I don’t know, violence is the right word. It’s, you know, that kind of action? could take sued violence, as you described. But yeah, in a positive sense. Yeah. Anyway, once you got to. Me, I’m working on it now. Yeah, good. I’m sorry. So I sidetrack you from, from finishing with. So after you own it, what do you do?

Lama Rod Owens 37:51

You own and you experienced that? Right? So we’re spilling into it. And then once you get enough of that, you know, another part of the agency, right comes up when we let it go?

Daniel Goleman 38:03

Well, what do you say to let it go? What are you letting go on? What are you keeping?

Lama Rod Owens 38:08

Well, I’m letting go of the fixation, right of, because I’ve owned it, I’ve experienced that. So I’m really into it, right, I’m moving through it. And then at some point, we just kind of have to like, let that go and come back to this experience of space in the mind. So you let it go. And then you move into the last piece, which is let it float. Right, which I that’s like my favorite part, actually. But like, when I let something go, I want to also really have this energy of letting it just float in my mind.

Daniel Goleman 38:52

So if what you’re naming and owning his, say, systemic bias or racial injustice, when you let it go, you don’t let go of the concern

Lama Rod Owens 39:08

about it. You don’t let go the concern, right, you need the space to get the perspective. Right, because you experienced that. That’s one perspective, you’re in it. But like, it’s hard to do something. That experience because if you’re experiencing something like bias, you’re going to also experience the guilts. And for most folks just being really in the guilt, it feels really hard to work through. But we still have to feel it. And so when I advise letting it go, then you’re able to get some space and say, Okay, I felt that. Okay, now, what else like what do I do now? What

Daniel Goleman 39:45

do I do? Yes, there’s a maximum systems theory that seems to apply somewhat, which is that the entity that can take information fully understand it most deeply and respond most agilely is basically the winner. That’s, that’s the best way to be. And it seems that that’s is what kind of what you mean by Let it go. Let go the part of your viewing it, it’s distorted. That’s Overleaf fixated as you said. But don’t give it up. Yeah. You still want to act, but you want to act clean. You want to act freely. I guess what you’re saying is that Yeah,

Lama Rod Owens 40:31

yeah, absolutely. I think the floating part is, it’s just letting it be there. Yeah. You know, it’s there. It’s floating in the mind, but I’m not attached to it, I see it. You know, I’m still in relationship to it. But I can still, I still have three days to do things. You talk about

Daniel Goleman 40:53

anger and trauma, and having trauma triggered, and then you give a practice for that, which is a meditation on anger. was kind of stunning. How can you meditate on anger in a positive way?

Lama Rod Owens 41:07

One of my beliefs is that if you’re going to do really hard work, that you need supports, and I think so many, some of the meditation methods is really about, okay, we’re going to do this, like, we’re going to lean into it, we’re going to feel it. And, yeah, some people can do that, you know, most people can’t. And so, I developed this, this practice of the seven homecomings, right, which is a benefactor practice, basically, you know, and I studied in a factor of practice with john McCroskey lemon. jhana years ago, he was my first benefactor teacher, right. And, and I’ve always held been a factor practice to be really important. So benefactor practice is a loving kindness practice or another practice, where we imagine receiving love or care or compassion from an imagined benefactor, someone you know, in our life, or someone we’ve ever had positive contact with. But you know, but it’s cultivating that energy and learning to deeply accept it. So as I say, drink it. You know, so that’s been an effective practice regular, you know, basic metta practices, going through phrases, and trying to generate that, that experience of kindness for ourselves. So, so, seven homecomings is just and more of an advanced benefactor practice, where I asked folks to, to bring in all these categories of benefactors, teachers, guides, communities, ancestors lineage, also evoke the earth Iraq, silence, I also evoke the energy, the power of Dharma, which I call wisdom texts. So I ask people to bring all of that into the space and to learn to like really absorb the energy of kindness, you know, and having that as a support, then I say, Okay, now, let’s lean into this anger. You know, it’s almost like someone’s holding you as you’re leaning over. Like that edge, you know, and so you feel so much more supported doing that.

Daniel Goleman 43:23

So you’re, you’re you’re experiencing your anger from a safe place? Yeah, yeah. A relatively safe place. Yes. Yeah. It’s interesting means that you include Earth. Yeah. You said that was part of your indigenous ancestry. Yeah. What do people get from Earth?

Lama Rod Owens 43:41

Yeah. groundedness. Really? You know, often, I noticed in my practice, that when I felt really unsettled, I wanted to go lie down. The Earth, on the floor. Oh, you know, I wanted something grounded, solid, and I was like, home, St. Earth are always holding us. Forget that.

Daniel Goleman 44:06

So in what sense can be love anger?

Lama Rod Owens 44:08

Yeah. Well, in in the sense that when I talk about love, I talk about acceptance. And so when I love my anger, I’m saying, Yeah, you’re here. Like, you’re exactly showing up, you know, and the only way that I can be in relationship with you, if I let you be here, you know, and that’s going to cut through this layer of aversion, you know, is either going to be a version or reactivity, that when I cut through with love, I don’t want to over react or react at all, but no, official way. I want to show up to let you be here. You know, and that’s what love is for me. In terms of anger.

Daniel Goleman 44:51

Lama Rod. I want to thank you so much for joining us on our podcast. Thank you. It’s been wonderful.

What Lama Rod is saying reminds me of a kind of big wake up I had in my teenage years, when I met a Nigerian anthropologist john ogbu, would come to my hometown in the Central Valley of California, to study the caste system in my town, I had been absolutely utterly oblivious to the fact that there was what amounted to an American caste system. And since then, there’s been a brilliant book written about caste in America has been became a bestseller. But back then, it was a radical idea. And he was really talking about systemic violence, systemic oppression, the fact that in my town, as across most of America, particularly groups were held down by the system, they couldn’t get loans, they couldn’t get mortgages, they couldn’t keep jobs, they were marginalized economically, and people were biased against them, there was prejudice, sometimes openly expressed, sometimes implicitly expressed, the schools they went to, were considered less good compared to the schools that people have privileged went to. And I have to say, including me, but what the key point was, the systemic violence is, I think, largely invisible, except to the victims of that violence. And that it’s only been recently when acts of that systemic violence have been spread on the internet, that people in general have become incensed by it,

Hanuman Goleman 46:50

there’s so much in what you just said, an important thing that I want to mention again, just to highlight is that the violence and oppression inherent in political or a social system, there’s always going to be a power elite, or somebody who has more access to power, it’s about privilege, what you were just saying, and that there’s an aspect of privilege, that is blind spots, it’s really important to understand privileges, and just the good things that happen to people in power, or to the power elite. You know, it’s not just the way that the system is weighted towards somebody privilege is also the ability to not pay attention. It’s such a beautiful example that you gave Dan, of the school that you went to, you didn’t even understand what was happening, because you didn’t have to look at it. And there’s so much that we don’t have to look at in this world, that if we did look at it, if we did know about it, we might want to do something about it, we might feel really differently. And so that piece of privilege that you were talking about, I think is really key to call out explicitly, because that’s just one thing that you were made aware of. But the thing about blind spots is that we don’t see them. And that’s one of the deep values of communication, of talking to other humans, from different backgrounds and different perspectives. You know, this is why it’s important to have more than one voice in the room. Why? why it’s important that everybody who’s impacted by a decision has a voice or can be heard in that decision making process.

In this last discussion, Dan and I talked about our privilege a lot. we’re privileged in a lot of ways, access to healthy food, healthcare, and education. I grew up in a town where I felt safe with my peers and safe with the police. My family and I had a safe place to be during the COVID-19 lockdown. All of these are areas in my life for which I am deeply grateful. And they are also areas of privilege for me. Each of them has made it easier to succeed. And without any one of them life is a struggle. What we didn’t talk about directly, though, was another privilege that Dan and I share. We are both white. Racial dynamics are deep in society and deep in our psyche, and can be difficult to talk about. But it’s important to acknowledge and name it directly so that we can address it properly. In the United States, white privilege undergirds all the basic human necessities that I mentioned as privileges, access to decent food, health care, education. And even just feeling safe. If you are white in the US, you are simply more likely to have these things. The important thing is that it’s not a coincidence. And it’s not that whole groups have inherent characteristics that keep them from success and well being. legal and financial systems produce the outcome. They were designed to end when a group disproportionately benefits from a system, and another group suffers disproportionately, that system is designed to produce inequity. We live in a country where white people are overwhelmingly more likely than black indigenous people of color to gain and amass financial wealth, and less likely to be arrested for committing the same crimes. Our systems are weighted both for the success of white people, and waited to undermine the success of most people of color. This is white privilege. A deep bow of gratitude to Shana and Lauren, the guests in the next segment, for pointing out this blind spot in the discussion between Dan and me. In act two, we take another look at the relationship between love and rage. This time through a segment we call connections, where we bring two people together to have a conversation on our theme, ai correspondent and all around badass Elizabeth Solomon reports.

Elizabeth Solomon 51:30

One of the criticisms of emotional intelligence has been that it seeks to ignore anger. competencies, like positive outlook or emotional balance have led to an assumption that the goal of Ei is to be nice or kind. And that in order to do this, we have to be contained or somewhat emotionally repressed. But this isn’t really what emotional intelligence is about. It’s much more about agency, about having the self awareness to understand what we are feeling, why we are feeling it, and then choose very intentionally how we want to respond. And the response part is key. It’s not about anger or no anger. It’s about claiming our anger, understanding the source of our rage, understanding where it lives in our body, and what our relationship to it actually is. And then making a conscious choice as to how we want to utilize it. It’s the difference between letting it consume us and using it as a constructive tool. In our next act, Shana Hammond and Lauren Henley sit down to discuss anger, leadership, race, equity and power. Shana is a certified emotional intelligence coach and the CEO of lead for liberation, formerly known as teach to lead. Lead for liberation is a leadership development organization dedicated to supporting leaders in leading through the lens of racial equity. She also runs Indigo women, a nine week professional development journey designed for black women executives and entrepreneurial leaders. Lauren is a consciousness coach, lead facilitator for the conscious racist, and since this recording has become the program director at LEED for liberation. If you want to learn more about Shana and Lauren, please see our episode notes for their full BIOS. Shana is currently recruiting participants for her next cohort of Indigo women. If you’re interested, you’ll want to apply now.

Lauren Henley 53:37

My name is Lauren Henley. And I consider myself a freedom coach. And I live in Chicago, Illinois.

Shayna Hammond 53:44

My name is Shayna Renee Hammon. I’m a leadership and life coach.

Lauren Henley 53:49

I just noticed as I sit here and look at you, I just have so much gratitude and appreciation for one this experience with you, but also just having you in my world. And I feel like knowing you is a real affirmation to me that the universe is for me and with me and ahead of me. So just want to express so much gratitude to be with you today.

Shayna Hammond 54:10

Receive that thank you and I have so much gratitude for you. I mean, we knew each other years and years and years ago in another context and it’s been so beautiful to get to know you now. I think both of us have been through a spiritual growth journey. And to see each other and kind of meet again now and see our work so beautifully complement each other has been amazing. And so I’m so so grateful for you so grateful for you saying yes to your work that you’ve been doing forever. And now doing more explicitly and boldly and loudly. It’s just really good to be in community with you. Feels like very, very Kindred.

Lauren Henley 54:52

Thank you. I’ve chills in my body. So I’d love to just start the conversation by asking you a question here. available? Yes, yeah. So you know, given like, you just have this longevity and depth in the field of emotional intelligence, also racial equity and leadership, like all of those realms are zones of genius for you. And I really want to understand better how is constructive anger played a role in all three of those areas,

Shayna Hammond 55:22

constructive anger. So it’s so interesting, because I think anger in of itself is probably what birthed some of this work, especially when it comes to racial equity work. Like we all know, you know, violence, and anger is the language of the unheard. And so sometimes, you know, it has taken a reaction in order for us to go back to the beginning and realize how we got here in the first place. And so when I think about constructive anger, especially with black women in leadership, feeling this pressure of suppressing anger and feeling really, you know, nervous about being kind of described as the angry black woman and anger, always kind of having a negative connotation to it. And I saw ways in which that cut off their their power and how it cut off my own. And when I was going through my own spiritual journey and growth, part of that was owning all sides of myself owning the justified anger, owning the sadness, owning all of the emotions. And it’s actually in that ownership, where I found myself again, and I found my power, and an action. I mean, excuse me, anger, and of itself, is the emotion of action. It’s the emotion that tells us what to do. It’s the it’s the emotion that wakes us up, we’re all waking up right now, we’re all being invited to wake up and raise our consciousness. And when I think about the work that I do, when you peel back all the layers, it’s about raising consciousness. And part of that is being conscious of your anger, as a black woman, as a white woman, as a white man, I think for far too long, we have suppressed anger, we have run away from it, when really, there’s so much to be learned from it. And even in the expression of emotional intelligence, sometimes, you know, it’s, it’s been in the past kind of spoken to in terms of managing anger, or disarming it, when really, we need to lean into it, we need to express it, we need to experience it, and then translate it and find what that translation power is about. For me, it’s coaching, right? It’s teaching, and, and what I’ve come to also understand about anger, you know, it’s really that it’s that peace of passion. I mean, anger and love is passion. So without that anger, you really don’t have a lot of the advancements that we’ve seen a lot of the, you know, amazing ideas and organizations have been born out of justified anger. And so, you know, when I think about the cross section of racial equity, of emotional intelligence, of education of leadership, it’s really how do you tap into that constructive anger? How do you engage instead of disarming conflicts? How do you engage in a healthy way, and such that people can express it so that you can get to real change, systemic change that we’re all looking for? And I think that it’s just time for us. And we’re being invited to really learn from that anger a little bit more instead of being scared of it?

Lauren Henley 58:38

Yeah, I just noticed, like a big wave of energy in my body when I listened to you. And I just want to, you know, kind of highlight some of the things I heard you say, and, you know, you I heard you say that anger is the language of the unheard that anger is a pathway to action and passion. It’s a pathway to power. And that in order for us to raise consciousness, we have to integrate all emotions, and we can’t say, oh, sadness is okay and fears, okay, but anger is not okay. And then specifically, in the experience of black women, the pattern that you were noticing of black women like holding their anger down or protecting, you know, other people to not fully speak up and how that has really come forward. And then it sounds like it’s really inspired you to step forward into your power.

Shayna Hammond 59:26

Yes. Very much so very much so. And it’s and it’s interesting, it sounds counterintuitive, but I actually experienced more joy. And I think it’s because I’m more authentic. You know, I have given myself permission to say yes, that actually is what I’m feeling. And then it’s helped me get to know myself in a different way. And you know, I’ve recently discovered yoga and other ways to just express it and and I dance a lot as well, and just kind of move it through my body, such that I can stand up and say whatever whatever it is, I need to say in a way that’s both true to myself, and in a way that can move the room and and potentially move organizations. And so, and it’s just I’m so glad that more and more people are kind of waking up to that. And, and what it’s also going to take is not just kind of those who have kind of been on the receiving end of immense pressure and oppression, to kind of take that step forward, but everyone, especially those and white dominant communities, white folks need to also be okay, right with their anger. And so I love to hear from you with the work that you’ve been doing for so long, and now really deliberately stepping in as a freedom coach, working in community with other white people. What does constructive anger mean? When it comes to being an ally, when it comes to being a white person who says, You know what, enough is enough, I’m here to do my work. I’m here to wake up. I’m here to take ownership of what’s mine and move. And so I’m curious, you know, what have you learned along the way, as you’re coaching and working when it comes to constructive anger, and the work that white folks need to do?

Lauren Henley 1:01:23

Yeah, I’d love to answer that. So a few things come to mind. One is that a good number of my clients who come to me to specifically work on their white fragility, or white women, I mean, Muslim majority, that’s just a data point. So a pattern that I see regularly, and what they’re coming towards is like, they’re in a fear and victimization pattern of like, I want to speak up, and I see that these things are wrong, and I don’t want to rock the boat, or I’m scared of the impact that that’s gonna have on other people or my relationships. And so in that way, they’re choosing other people’s comfort under over their own. I think it’s also a way that like patriarchal consciousness, like meets, you know, racial consciousness in terms of the ways that as women, we have made it wrong to be angry in general, to not disrupt the status quo. And so for me, and even in my own practice, it’s about being an integrity with myself, if something feels wrong to me, in my body, if something feels off, then I’m going to choose to speak what’s true for me over the discomfort of the other person. And that can be from anger sometimes. And it can even be a little bit messy. And so I noticed that, for me, and for other people that I coach, we have to take this step, to learn a new muscle and first say something, you know, and then reflect on it, you know, maybe next time I’ll say it a different way or whatever. But to me, the first step is just accepting yourself for where you are and what you need to say. and allowing that anger, like you said, I think it’s a pathway to power I think, if we’re really going to make a difference and disrupt this racial this system that is so deep. Anger is, like the only way.

Shayna Hammond 1:03:12

So much of that hits in so many different ways. And something that was really interesting that you said, um, was this notion of white women, feeling of not wanting to make other people feel uncomfortable? And that struck me because so many people of color, especially in the workplace, have to spend so much energy and making sure that they don’t make white women and white men uncomfortable? So I’m just curious if you can kind of peel back those layers we have, you know, it’s just so interesting that so much of what’s happening, is this kind of tiptoeing around comfort? And can you kind of peel back the layers? What has that been like for your clients? For one,

Lauren Henley 1:03:57

I think it’s really interesting to ask the question, like, who defined comfort and who are we catering to? Right? And that is a really big question. And those social norms and looking at that, but, you know, it has been a story that I have is that why women one way that we have gotten attention to the patriarchy is through victimization, and white women’s tears, that, you know, we at some point in our own attempt to survive, like made an internalized awareness. Like if I get angry and I challenge, then I get shut down. But if I cry, then I get attention. But we also know that throughout history, why women’s tears have been used to repress and even cause violence against the black community. So it’s like so intricate to me that this dance is happening, right? Where, like women, women who want to be allies is who I’m really speaking specifically to women who want to be allies are having to truly look at how they’ve used their tears and Their apathy and their powerlessness to get their own way to get the things that they needed to, to kind of basically manipulate situations without disrupting those situations. And so to be a white ally, as a woman, I think, is actually saying, like, I’m not going to play that game anymore into my truth and my power, and I’m going to accept the consequences or whatever impact it has on those around me. Yeah.

Shayna Hammond 1:05:31

And I’m just, you know, grateful for more and more spaces, like the ones you’re offering popping up for specifically, white people, white women, white men to do this work, I get the question a lot. It’s something after eight years of teaching, and leading and holding space for different organizations around the world, one of the biggest things that I’ve learned along the way my team has learned along the way, is that this work of raising consciousness, specifically through the lens of racial equity, really requires it to be done in affinity and with other people who culturally identify closely to you. Because to your point, so much of sometimes we would watch and interracial groups I would watch. And you know, some white women in particular kind of come into their own have awarenesses have different breakthroughs. And of course, tears and different things would happen, that would then in turn, unintentionally, harm the people of color in the room. And oftentimes, it was their work that got centered. And then the work of really healing internalized racism, internalized patriarchy, was put to the side. And so something I’ve just learned is that so much of this healing, and work really does need to be done. Much of it, not all of it, but much of it, and affinity even, you know, both the interpersonal as well as some of the systemic pieces. So glad you’re holding that space, we’re continuing to hold more spaces like that, I’m so glad you’re doing that with us at teacherly. could not be more excited about that. And it also leads me to another wondering. And something we often get, I get asked to sometimes my teammates get asked, which is this idea of ally ship and what it really means to be an ally. Um, and you know, who gets to say, you know, whether you are, whether you are or not, and how so much of the harm being done to lots of people on the margins has been around fragility, and, and has been kind of held up through white fragility. And so I’d love to hear a little bit more about what your work specifically does around white fragility, and and what kind of and how you see that work having an impact systemically? Well, I

Lauren Henley 1:08:03

totally agree with you when I was working in spaces that weren’t affinity based, like the emotional labor and people of color in that space was just giant. And, you know, it really wasn’t a progressive conversation, because you have people of color who are at a high level of awareness, because they’ve lived this at their whole life, and they’re ready to talk about something that’s way up here. And then you have some people that are just entering the conversation for the first time, and processing a lot of things. So that’s really what led me to start moving in the direction and when white fragility came out, it was just such a stamp to me the way that she outlines the patterns that we see, in way the defensiveness and powerlessness comes up. When we talk to white people about race. It’s like amazing, it’s, it’s so predictable. And so, for me, the white affinity space in the work around white fragility is first about exactly what you’re speaking to is about starting with consciousness. You know, in early in my career, I was so much focused on action around justice. And of course, I still believe in action. But I realized that if you go into action, with a consciousness that’s highly colonized, that’s highly white supremacists, you’re actually just going to recreate the systems that you even came to change. And so what I saw when I started doing these white affinity spaces was one people being really radically honest about the racist thoughts that they were having, you know, racist family members, things that would be they felt ashamed to share but as we know, in consciousness, everything has to be out in the open to work with it, right. And then the other piece was like really coming back into their bodies. whiteness is such an intellectual game is the way that I would put it, it’s like, you know, perfectionism, even even in this term in the current context where people want to wake up around this, it’s more like I want to get an A in Racism, I’m gonna go read all the books in all the podcasts. And I’m not doubting that. But if you don’t physically shift to an embodiment practice where you’re breaking down how oppression and colonization lives in your body, how if you can’t be embodied with a person of color and truly feel them and feel their experience, then I don’t think that we’re actually going to expand, I think it’s likely we’re just going to repeat the same patterns. And so just to summarize, like, that’s what the white affinity space it says, we come together with an intention and agreement to wake up our consciousness around the ways that we’ve been in denial about the ways that we’ve been fragile about the ways that we’ve been racist about the ways that we’ve been whites have, you know, been a part of white supremacy, and that is no easy task. And like, white people can choose from privilege to skip over that conversation, it’s a choice for them to engage in that.

Shayna Hammond 1:10:56

Yeah, I like that you mentioned healing, we all need to heal. And you know, just why I am so passionate, especially of how centering black women, and, you know, you mentioned the healing that’s necessary for white women. And just kind of the disjointedness, we experienced as black women, as black people, other people who’ve been marginalized in different ways. And, you know, we ourselves have been fractured. And it’s, you know, it’s a time for, you know, really coming back to that integrate itself. And, and which is why it’s so important for us to be able to have a safe container where we can do that, where we can reintegrate those pieces of ourselves that either knowingly or unknowingly, we left behind in pursuit of a definition, maybe of success that was given to us through social conditioning, maybe through our parents, through white supremacy, etc. And, you know, that’s really what this work is about. It’s about calling in healing. And it’s so interesting that you said, We’re both also educators. And when you were talking, I went back to a conference I went two years ago, where the grounding question was something around, you know, an education. What’s the next innovation or something? And I spoke without thinking, just write up. I said, healing really loudly. And there were a couple people who nodded, but most people were like, healing like, that has nothing to do with Ed Tech. How do you scale healing? What does that even look like? And then here we are in this interesting place where we are in between paradigms, and a new paradigm is still emerging. And so many people are being called now to heal. And I do believe it happens in two ways it happens, you know, personally interpersonally you know, you kind of doing your own work. And you know, there’s a systemic healing as well, that’s being called in around systems and redistributing power. And so when I also think about healing, I think, you know, I think about our folks doing that work. Constantly. We’ve been doing that work, and we’re now learning how to do it more expansively. The question always is right, like, what does this look like when it comes to institutions and systems? And and really, truly redistributing power? And how, how are we going to actually call people in? Or take power? Right? Because what really needs to happen? systemically, we have to see some shifting of those, making sure the the people that we’re serving are the ones who are who have the decision making power, who are making decisions, who who are, you know, also influencing other people and so I’m, I also just think about that conversation quite a bit. It’s so interesting when you said that it brought it back up, like how do you scale healing? And what does that look like on a grand scale? When you think about healing as innovation and both education and and and other institutions as well? What comes up for you?

Lauren Henley 1:14:19

Yeah, I have again, chills all over my body. I really similar experience of like seeing the healing, education and the necessity for that, um, I see it I when it comes up as I see it in circles, I see it as from the top down in the bottom up like leadership teams committing to becoming relational. I feel like that in this innovation looks like learning to be human. And like as an individual, I have gone through this like transformational journey about learning how to really be human to be in my body to be in my feelings, and then to be with other people and the system. Instructors are almost as if has almost treated us as humans as if we’re robots. Right? We’re not really expected to eat or sleep very much, or see our families or, you know, and I think even in the current pandemic, and all the changes that have been happening, people are really waking up to how they haven’t been living very human. And so now, one, I’m called to be a human. And then the question that’s going to break down the systems is what does it look like to be human in an organization? What does it look like to prioritize humanity in an organization, and therefore an all white organization? And we’re looking around and saying, why isn’t this place more diverse? Like, what commitment Are we going to make to our own healing and our own conscious awakening into our body so that if we bring in people of color, we bring in other humans, other types of humans into our organization, that it’s a safe and loving place where they can be empowered and thrive. So all of that comes up around healing, and at the end of the day, to me, it’s about prioritizing people and relationships.

Shayna Hammond 1:16:04

Yeah, I cannot, cannot agree more. It’s interesting I was, I was going through a strategic planning process. And we were trying to basically describe, you know, who we are and what we do. And we kept coming back to human it’s a humanistic approach to leadership development, and it’s one in the same. And as a, you know, a leader, if you’re charged with, you know, leading an organization, leading the community leading a movement, how important it is to first honor your own humanity, so that other people can honor theirs. And if the leaders don’t, you know, honor their human humanity, then it’s really, really hard for others. Another interesting kind of trend that I’ve noticed over the years, working with so many different organizations is this notion of, at times the organization’s consciousness, the staff members being higher and more kind of ready for this human approach, then sometimes their senior leadership, their senior leadership team, and I, you know, it makes me wonder, you know, why is that? Why am I seeing that trend of kind of staff members who are sometimes many times more proximate to maybe the clients they’re serving, or students, they’re serving, you know, really ready to shake things up, switch things around move systems, and I see much more fear, oftentimes, when I get to senior leadership teams and wanting to kind of try something new. And really, you know, and sometimes it gets kind of boiled down to this false tension of human meaning, lowering expectations, or not having as grand of outcomes, right, if you will,

Lauren Henley 1:17:54

Less sufficient,

Shayna Hammond 1:17:56

exactly less efficient. When really have we really been efficient? Usually, we spend so much time cleaning up, and backpedaling, because the decisions that we rushed to make, were not the best ones, they were not really truly in service of the people, we said we were serving, they were more so in service maybe of fear. And so, um, I don’t know, I just I think about that a lot. I encounter that a lot. And, and what I’m excited about though, is as we continue to shift to work more in affinity with our clients, and I am starting to see and hopefully eight years later, I can say, you know, I see even more that kind of gap closing. And I see more leadership teams stepping up and saying, you know what, this is where we need to go. And and they prioritize, you know, their work as well. And and can move with more conviction and more confidence?

Lauren Henley 1:18:52

Well, I think that I think about when you say that is like kind of what we’ve seen a lot in the current climate and the way that we have seen policies, changes at the state level. And the idea that like when from the bottom up when we collectively agree and put pressure on leadership teams, when clients ask more of the people that they are paying to work with, like the leadership team is forced to readjust and change. And sometimes those motivations are capital, they are political gain, but it’s so pressure from the bottom up. And so I think that’s what affinity spaces can really do for organizations is create alignment and consensus in a way that people can move forward collectively to ask for change in their organizations and disrupt the power structures that happen in a hierarchical organizational construct, right where the people at the top holds so much power and that’s really what we’re trying to shift even as a country I would think is that no longer is the hierarchical contract going to really work. It’s not even going to allow To survive, we have to embrace more of a human centered design construct where we bring in the people that we’re serving to be a part of the design where we’re designing for the marginalized. And that’s our priority, assuming that everyone else will be served when we prioritize that, and then last, like letting it emerge, because we haven’t done it before. You know, this is a new way of being. And so a big part of white supremacy, I think is like, I want to control the outcome, I want to clear strategy, like, I’m not willing to step into the unknown, and that I just don’t actually know how any organization will survive without stepping into the unknown in this new climate. And it also, I wanted to kind of go back to this new focus that you’ve shifted and teach from teacher lead to Shana Renee, you know, that seems like it’s been a very emergent process. And it’s been very based in like Human Centered Design and thinking about where you want to place power and influence. So I’d love to hear about your decision to focus exclusively on black women in leadership.

Shayna Hammond 1:21:06