S1E4 Are The Kids Alright? The Impact of Social Emotional Learning (SEL)

Initially, we set out to talk about Social Emotional Learning (SEL) at a time when millions of kids have been home, attending school online and missing out on valuable time with their peers. But we quickly realized COVID is far from the only thing kids and educators are grappling with—racial inequity, trauma, isolation, social unrest, and overworked parents are a significant part of the equation.

In this episode we talk with Adjunct Professor at Columbia University, Linda Lantieri, Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) specialist, Amber Pleasant and early career High School teacher, Ben Chase— three people actively involved with implementing and evaluating SEL in the classroom.

Our Guests

Amber Pleasant

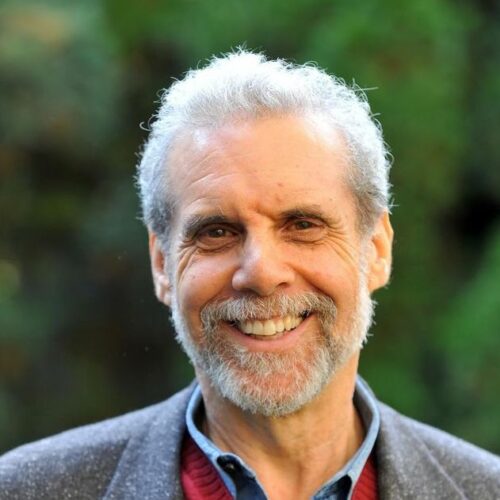

Linda Lantieri

Linda Lantieri, MA has been in the field of education for almost 50 years in a variety of capacities: classroom teacher, assistant principal, director of a middle school in East Harlem, and faculty member at Hunter College and presently at Teachers College, Columbia University. She is a Fulbright Scholar and internationally known speaker in the areas of Social and Emotional Learning, Contemplative Teaching and Learning and Spirituality in k-12 Education.

Linda has recently cofounded the Transformative Educational Leadership (TEL) Program for educational leaders who desire to lead from the inside out by integrating Mindfulness and Social, Emotional & Ethical Learning through an equity lens in the service of systematic change in education. She currently serves as the Senior Program Advisor for TEL.

Linda is also one of the co-founders and presently a Senior District Advisor for the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL). She is also core faculty of the Spirituality Mind Body Intensive which is part of a special M.A. Degree Program at Teachers College, Columbia University. She has been involved with designing and leading the concentration in k-12 Spirituality in Education since its beginning in 2014.

Linda is the author of numerous articles and book chapters and coauthor of Waging Peace in Our Schools (Beacon Press, 1996) editor of Schools with Spirit: Nurturing the Inner Lives of Children and Teachers (Beacon Press, 2001), author of Building Emotional Intelligence: Practices to Cultivate Inner Resilience in Children (Sounds True, 2008, 2014) and coauthor of Nurturing Gratitude From the Inside Out: 30 Activities for Grades k-8 (Greater Good Science Center, 2017). She is a Senior Scholar at the Fetzer Institute and a Fellow of the George Lucas Educational Foundation.

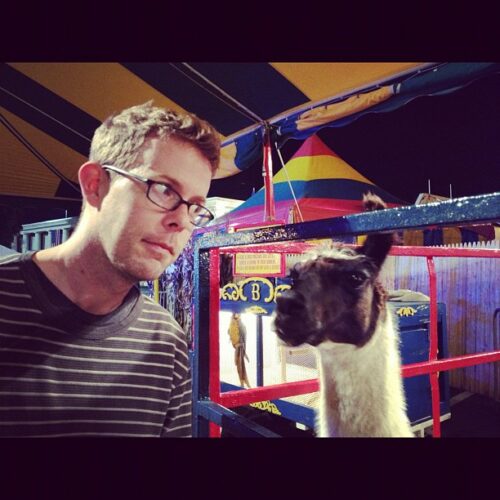

Ben Chase

Ben is a second year English teacher at Noble High School (public school) in Southern Maine. He proudly teaches in that school’s alternative program, Multiple Pathways, where they have permission to do school differently and to use the word “love.” He is surrounded by amazing educators, both in the program and down the hall, who he learns from everyday. Additionally, he is a student (and a fellow) in the Master of Arts in Teaching, Teacher Leadership program at Mount Holyoke College. If you’d like to get in touch, you can reach him at chase.b.nh@gmail.com.

Resources

The following resources were referenced in today’s episode:

- Triple Focus: A New Approach to Education, a book by Daniel Goleman and Peter Senge.

- Support our podcast by becoming a monthly Patron.

- The Collaborative for Academic and Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

- Transformative SEL as a Lever for Equity & Social Justice

- The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions.

- Bringing Humanity to the Virtual Classroom: Lessons Learned From My Desk (original publication by Great Schools Partnership)

Subscribe to the podcast:

Subscribe now and sign up for our newsletter to get notified as new episodes are released.

Have feedback? We want to hear it! Submit a Voicemail.

Episode Credits:

This show is brought to you by our co-hosts Daniel Goleman, and Hanuman Goleman and is sponsored by Key Step Media, your source for personal and professional development materials focused on mindfulness leadership and emotional intelligence.

- Special thanks to Pippa, whose voice you heard at the top of the show.

- This episode was written and produced by Elizabeth Solomon and Gabriela Acosta.

- Episode art and production support by Bryant Johnson.

- Theme music by Amber Ojeda.

Have questions or feedback? Send us a voicemail using our Speakpipe app!

Transcript

For full episode transcript and links to resources referenced in today’s episode visit our episode notes on our website here.

Gaby Acosta 0:00

Can you think of another example of a time that you’ve had really strong feelings?

Pippa 0:04

Right now during the Coronavirus? I’m having a really strong feeling. It’s a good feeling. And it’s bad because I’m glad we’re not going to school because if I went to school, I would get really sick. And I’m sad that I don’t get to see my friends and family.

Gaby Acosta 0:20

Has it been helping you to think about that, how the two sides of the Coronavirus and how it helps you in some ways?

Pippa 0:27

It helps me because it helps me from not getting sick. And it doesn’t help me because I’m not learning right now because I’m not at school. Well, I was learning because I was doing math at home, but *sighs* I’m still not learning much.

Gaby Acosta 0:46

Yeah, it’s a very different kind of learning huh?

Pippa 0:49

distance learning.

Daniel Goleman 1:05

I’m Daniel Goleman.

Hanuman Goleman 1:06

And I’m Hanuman Goleman.

Daniel Goleman 1:08

You’re listening to first person plural, emotional intelligence and beyond. Today, we’re looking at what we call social emotional learning, or SEL, why it’s even more important for kids in times of uncertainty and change, and how educators and parents can continue to support SEL development when their kids are going to school online.

Hanuman Goleman 1:32

So my children are five and three right now. So the five year old is in kindergarten, and she’s been online in kindergarten the whole year. And keeping kindergarteners engaged in a computer screen is an absurd prospect. The teachers amazing does an amazing job of it. But wrangling virtually wrangling whatever it is 12 five year olds is an unreasonable prospect, you know, Sujata can get on zoom for a little bit and check in sort of touch in with the class and peers that she will meet next year. But this year, there isn’t a social element to it, they’re not developed in the way that they interact casually. Through the screen, we’re very, very fortunate, we were able to get involved in like a makeshift daycare. So through that the kids are getting some social interaction, and that I feel solid about that. But at five years old, I’m just not as worried about math and reading. And these things as I am developing interest in learning and interest in the world around them and interest in themselves. I trust my kids, if I give them the inner tools to work with, that, they will become themselves in exactly the way that they are meant to be. And it’s not my job to tell them who they are. But it is my job to create the conditions at least for them to develop the capacities and the tools to navigate the world and thrive in the world.

Daniel Goleman 3:29

So, you know, these are my grandkids and I love them. And I want them to grow up really, you know, with everything that they’ll need to navigate life. And it’s important, of course, that kids learn academics. There’s no question about that. But the other side of it is very important too. And that is how you handle your emotions, how you get along with other kids, how you empathize how you tune in to them. And kids learn that from their interactions with other people. So being online, as Hanuman was saying, it’s just not the same as being in a classroom with other five year olds. We don’t know what the outcome will be. I’m optimistic because the brain and in children are very adept at making up for lost time, and learning lessons quickly that they have skipped, particularly in their emotional and social lives. So I also feel that it’s a very big omission for schools to ignore this aspect of development. That’s why we developed social and emotional learning to be sure every child would have the chance to get it right.

For a long time, schools had a major gap. They were focusing on academics and on cognitive abilities, but ignoring social emotional abilities, which have far reaching benefits in both school and life. There was a major study done looking at schools that have SEL programs and those that don’t. This massive study of 270,000 students found there were several positive effects of participating in SEL. First, prosocial behavior, like behaving well in class liking school, good attendance increased by 10%. At the same time, antisocial behavior, things like misbehaving in class violence, bullying dropped about 10%. Most interesting was that academic achievement test scores went up by 11%. Of course, these benefits flow into kids lives outside of a school setting, having positive social implications in their interactions with their friends and their families at home.

Social emotional learning also takes advantage of a neurological fact that the human brain grows and develops and becomes anatomically mature throughout childhood and adolescence, ending in the mid 20s. This is a window of opportunity for us to help our children get self management, self awareness, empathy and social skills from an early age, and that will help them thrive through their entire lives.

Hanuman Goleman 6:35

So far on the show, we’ve looked at a few aspects of emotional intelligence and some ways they play out in adult lives, at work and at home. But what does emotional intelligence look like for children, particularly in K-12 education, both generally and specifically during this pandemic? As a parent, I want to understand what skills and orientation our kids need to develop in order to be happy and thrive throughout their life. Dan explores this question and more in our first act.

Daniel Goleman 7:11

I’m Daniel Goleman. And my guest today is Linda Lantieri. Quite a wonderful old friend, someone I’ve known ever since I got interested in the area of emotional intelligence because Linda was a pioneer in what we now call social emotional learning. But when I first was writing for The New York Times about this, and then wrote the book, emotional intelligence, I turned to Linda because back then she was with an outfit called educators for social responsibility. And I really, that was one of the prototypic SEL curriculum, even though it didn’t have that label. Linda, first welcome. Thank you for being here

Linda Lantieri 7:49

Thank you Dan.

Daniel Goleman 7:50

And if we could go back in time, let’s, I’d love to hear from you your progression from you know, those early, early days before we had the term social emotional learning to what you’re doing now and what the highlights had been in between.

Linda Lantieri 8:10

Yeah, I was actually at the Central Board of Ed at the time you and I met, and I was working with educators from social responsibility. And that particular school district had many members that went to this conference on living in the nuclear age and the trauma that was happening for kids around that. And this particular school district got together and invited myself and the executive director Tom Roderick, of educators for social responsibility. Also, there was a growing violence problem. And so the combination of all of that we began to create the curriculum resolving conflict creatively. And that was going on for a while until you and I met through a very unfortunate incident. There was a shooting at Thomas Jefferson High School in Brooklyn, New York. And as the chancellor at that time, I actually had to go to the teacher who was shot, who is already in a hospital room with a bullet in his head. He lived. Another student was shot and did not live. And there I was trying to help the principal and young people make sense out of that. And you were a writer at the New York Times at the time, as you remember,

Daniel Goleman 9:36

As I remembered I wrote an article and I use the term emotional literacy first time, then what happened?

Linda Lantieri 9:44

Well, what happened is you talked about our program, and we connected and then not long after that, a small group of us including the both of us and Carnegie Foundation at that time and Tim Shriver and Eileen Rockefeller Growald and a couple of others came together and began to ask ourselves is this set of knowledge and concepts need to be a field? And is it a field, and then your book came out, of course, Emotional Intelligence, and that changed everything. And we began to at least be aware of the role that emotions are playing in our lives. And of course, as you know, we continue to meet in, in this group in a very informal way, and eventually became castle, the collaborative for academic, social and emotional learning. I’d like to say there, one of the valuable members was Roger Weissberg, absolutely Yale, then who was a community psychologist and a researcher, Roger made sure that this movement was backed up by well done research, which I think is one of its strengths from the start. And there was also Mark Greenberg, who had a prototype also, once we started, though, it became a magnet, wouldn’t you say? People came out of the woodwork. I was working in 14 different school districts in the country. And at that point, we were thinking whole school, whole district model, we were thinking in that way already, then several of the early SEL programs were on the right track. But we needed a bigger guidance around how this field could grow, and especially how it could grow based on the research that we began to have. So that was very key for CASEL to play that role in the field, there’s no question about it.

Daniel Goleman 11:44

I think it’s important for listeners to explain what SEL is there five main dimensions, one is self awareness. One is managing your emotions. Another is empathy, understanding what other people feel. And then the fourth is healthy relationships that come out of all of those first three, and then using that to make good personal decisions in your life. You know, like for a 12 year old or 14 year old it might be How can I say no to drugs and keep my friends? Right? You know, and one of the things I found when I visited into early program, it was one that Roger Weissberg had designed for the New Haven schools, called Social Development is that the kids there loved it, because it was about them. It was about problems. And I think that that’s always been a strength is that teachers find they can teach better, because kids can manage themselves better. And students find, hey, this is helping me in my life.

Linda Lantieri 12:48

Exactly. Exactly. It’s life skills, really, isn’t it?

Daniel Goleman 12:52

Yes,

Linda Lantieri 12:52

It’s things we all need no matter what. And, and even more so today, needless to say, of what is going on now, in our world. Those Questions.

Daniel Goleman 13:06

I remember you helped me visit a school that you had been advising, I believe, and they were doing something called breathing buddies, which was from audio that I did for you with a book that you had designed for this use, where I help kids focus on their breath and watch it rise and fall. It was basically mindfulness for seven year old

Linda Lantieri 13:32

Yeah, yeah,

Daniel Goleman 13:32

They loved it. But I think that one of the things that is striking about that school, I remember a teacher said, One day a girl came in very upset. I said, What’s wrong? And she said, I just saw someone who was shot. And the teacher said to the class, how many of you know someone who’s been shot? every hand went up?

Linda Lantieri 13:51

Yeah. Well, you you’re thinking of a school, it’s been been doing the work of SEL for a long time, and they live in a neighborhood that is really high poverty and, and low in the resources that they need. And and they’re also really working hard to be there for kids, you know, and yes, all of the kids in that neighborhood probably have seen something like a shooting. And it’s trauma that kids are living with today, a variety of kinds of drama. In some cases, it’s sustained trauma, you know, that’s poverty, as some of those young people were experiencing that was a sustained way of living that is traumatic, and I think certainly, emotional connectedness can buffer some of that and social connectedness and then some of the skills we develop, particularly around regulating what’s coming up in their body, knowing how to get to that Resilience own, that calm, disown, and know what that feels like in the body. You know, one of the things we know about resilience, as we said before that it’s not a single factor, you know, we are we feel different levels of resilience. So, resilience is not a specific amount that we all have, you know, when the COVID virus said, we were all at different levels of resilience, some of us had contributed to the bank of our own resilience quite a bit. And so we started to roll with the punches. But other people clearly benefited from social emotional learning. Before the COVID experience happened, we were dealing with the first pandemic, which was the racial inequity. And so depending on your race, quite honestly, and the experiences you’ve had with that, whether or not you as a teacher, are of color and have to deal with a microaggression, etc, or not. And then this hits, also them together, the dual pandemic. And for some teachers, if they were already having a tough time, they already were experiencing trauma of some kind, there’s not much left. And so I think we’re becoming more aware that we can’t go right to the kids. As with anything like this, we have to realize that our kids will get as well as the teachers are. Well, and so we have to stop sometimes and say, What self care is happening for the teachers? Can we provide some of that? Will we provide some of that as as part of PD, and we try to do the best we can, given whatever the trauma is.

Daniel Goleman 17:06

So you’re mentioning two kinds of trauma kids are facing today. One is kids who are growing up in poverty, with a lot of violence around them and maybe in their lives. The other is the collective trauma of staying home. COVID afraid of the virus, all of that? How could this kind of program, social emotional learning, help kids become more resilient with these kinds of trauma?

Linda Lantieri 17:36

Well, I think first of all, we have to be aware that we could do this virtually, it’s unfortunate that we use the word socially distant, we really mean physically distant.

Daniel Goleman 17:46

In our family, we call it a friendly distance.

Linda Lantieri 17:49

I think we could call it friendly or physically distant than the word socially or emotionally, because that’s not what we want to do. We want to be emotionally close. Right? We won’t even be socially close. So how we got into social distancing in versus its physical distancing. That’s what we’re asking six feet of physical distancing. Socially, I want to be connecting to you in some way, you know, and teachers are doing that very strongly. And SEL programs, so many of them are having young people talk to each other, are engaging lessons that can happen also online.

Daniel Goleman 18:30

Could you give an example of what one of them might be? Sure, just

Linda Lantieri 18:34

the other day? I, I saw a class I heard of actually, one of the classes that we’re doing an activity I do all the time, called, what’s the news that actually comes from Responsive Classroom? You say, Good afternoon, and a kid uses their name to a kid, let’s say good afternoon, Thomas. And Thomas’s Good afternoon, back to Susan. And then Thomas says, What’s the news? And you know, we could do it even right now.

Daniel Goleman 19:11

So that opens a conversation between kids,

Linda Lantieri 19:14

you know, and then they invite the next person, but basically, a lot of the rituals around getting to know one another, a lot of the rituals about communication that are part of actual curricula of SEL are the things we should be using really, we need to be using, and many teachers are using.

Daniel Goleman 19:37

So is there anything trauma specific in that mix?

Linda Lantieri 19:41

I think more and more teachers are becoming trauma sensitive, and therefore healing centered in their work. And by that, I mean, in some curricula, as you perhaps know a little Bit of called the C learning curriculum, which is a social, emotional and ethical learning out of Emory University. There’s some curriculum that really, really pays attention very directly, you know, we have the adverse childhood experiences,

Daniel Goleman 20:17

oh, what is an example of an adverse childhood experience

Linda Lantieri 20:20

Alcoholism in the family abuse, abuse and neglect, divorce. So we found out from something called the aces study, adverse childhood experience study that, wow, when our kids get to fifth grade, they have two or three of those 11 of those, all kids have had trauma. So as a result, I think we we teach more through that lens. And the reason I brought up the C curriculum, is that that teaching is very direct in that they teach about the resilience zone, the low zone, the high zone, how to get into the resilience zone, they teach kids things that I wish I would have learned when I was a kid, like what, so one of them is grounding. And grounding is simply using a physical object in some way to literally ground to touch, it might be a piece of jewelry you care about, or it might be a wallet, you go back and forth on when you’re feeling a little agitated. And now we actually have that, in hallways, we have two little places where kids can put their feet and they push against the wall, and it says something like, Can you can you do five pushes against the wall and back? See how you feel? You know? That’s an example of grounding.

Daniel Goleman 21:58

So is that one of the things you find most interesting in K to 12? Education these days?

Linda Lantieri 22:04

Yes, that is one of the things I’m very excited about, and also much more of a focus on equity, and cultural competence.

Daniel Goleman 22:14

What would that look like K to 12k?

Linda Lantieri 22:17

K-12 would look like first, making sure kids of all ages have a clear history of what has happened in our country in particular, particularly around race, slavery, etc. that we have an historical knowledge of how socially created races, and all of those things, then do things that are more culturally competent, where we share our backgrounds with each other, where we tell each other what is helpful and what isn’t helpful, where we begin to have more of a sensitivity toward each other. And that work has been very, very meaningful. And, you know, lately, as you probably know, I’ve been doing work with higher level leaders in the field of education. You know, when leaders get up to a certain place, you know, they’re ahead of SEL have a whole district, it’s sort of like, well, what’s their professional development, you know, we’ll forget that they need. And we have a wonderful cadre of these leaders every other year with our program and transformative educational leadership. And it’s been great to really support those leaders in those threads.

Daniel Goleman 23:41

So what do you think is needed to grow the SEL field?

Linda Lantieri 23:45

I think what’s needed to grow the SEL field is what we have been starting to do, which is to really, really pay attention to issues of racial justice, and the SDL world. There’s five competencies, we’re looking at each of those competencies and asking ourselves, what would it mean if we were culturally competent in that?

Daniel Goleman 24:21

Linda asked me to give a talk via zoom to her group of transformational education leaders. These are people who are involved in SEL in one way or another, and have a high position in their school district, their administrators, sometimes their teachers, I was struck by how diverse that group is. That itself is very important that the people who are leading this movement and her speaking for it, embody difference. One of the messages that you want to deliver in SEL is a comfort with diversity and how natural that is how normal it is. SEL is the natural container for dealing with bias for improving diversity for advocating for inclusion, because these are social issues, and they’re emotional issues. They’re not cognitive academic issues, actually, they have to do with how we relate to other people and to how we have an act on our don’t, our own biases, or even implicit unconscious biases.

Hanuman Goleman 25:34

What she leads with here, I think, is just so important, and it aligns with personal transformation. And in this way, society goes through the same thing. And that’s just around truth. We, we can’t transform, we can’t, we can’t become something new until we are honest with ourselves about who we are, and where we’ve come from. And that’s true in personal psychology. And I think that that’s true in society as well. And you can see that with truth and reconciliation. In Rwanda. You know, these places that have really gone through this, this process of this painful process of bringing the truth of our situation to light so that we can be properly addressed. And until we do that, it’s just sitting in the shadows whispering in our ears.

Initially, when we were developing this episode, we set out to talk about social emotional learning, at a time when millions of kids had been home, attending school online, and missing out on valuable time with their peers. But equally important is to look beyond COVID to understand the social and emotional conditions, impacting students and educators every day, that make SEL difficult, and that have been amplified by the COVID pandemic, and also how SEL can be an important component of addressing some of these very issues. enact to first person plural correspondent Gabby Acosta reports.

Gaby Acosta 27:32

As Linda says in Act One, COVID-19 isn’t the only pandemic we’ve been facing—pervasive bias, inequity and racism are diseases of their own. They seep through our systems, impacting people’s ability to access resources, opportunities, and cultivate greater resilience. Our team wanted to take a deeper look at a specific example, where SEL is being applied to create more access and inclusion for all students and our education system. In the next act, I speak with Amber Pleasant, a social and emotional learning (SEL) specialist in Austin Independent School District, which she calls ISD. Amber tells us about the journey to integrate SEL, culturally responsive pedagogy, and distributive leadership as tools for addressing systemic oppression across her district. Here’s my conversation with Amber.

So I wanted to start with a couple of definitions. Actually. You we talked about transformative SEL. Could you actually define for those who don’t know what transformative SEL is? And also why is it different than just SEL?

Amber Pleasant 28:52

Well, castle does a great job of defining transformative SEL and here’s what stands out to me. You know, SEL it’s is a process. And there’s the the original definition really focuses on the competencies, right, and of self awareness and social awareness and relationship skills, self management, right? Transformative SEL acknowledges that there are oppressive systems and structures that exist, and that people need to work in relationship with each other to be able to approach equity challenges.

Gaby Acosta 29:36

Why is it necessary to adapt transformative SEL and what existed before what we now call transformative SEL?

Amber Pleasant 29:46

As an SEL specialist, I get to walk through a lot of campuses or at least before the pandemic, I got to walk through a lot of campuses and see teachers and kids and folks in the learning in the learning community. And kids experience a lot of injustice, adults experience a lot of injustice, injustice makes people feel really big feelings. So one way that that kind of the older version of SEL might approach that is like, well, you just need to manage, you need to manage those strong feelings, transformative SEL instead acknowledges that it is entirely justified to feel angry, frustrated, hurt, when you are being marginalized and oppressed and in the face of injustice. And so I think that’s a really big, big differences, understanding that and acknowledging as well, that, you know, adults have to commit to continuing their own social and emotional learning, development, and that the system and structures that we work within, we have to pay attention to those, we have to shift the practices within schools, within school systems within our communities, so that we’re not seeing so many injustices that we can’t predict which kids will succeed, which kids will be disciplined, we shouldn’t be able to have these predictive factors, right. And so transformative SEL is attentive to the need for systemic shifts and changes and evolutions. And it’s not just about this the individual child, or even adult who who needs to change.

Gaby Acosta

Is it different than social justice?

Amber Pleasant

Oh that’s a good question. Yeah, it’s different because transformative SEL requires the inside out approach to developing a culturally proficient lens. So there’s unnecessary work, self reflective work, that teachers educators need to do. And it’s not just about getting a diverse set of books in the library, which is more of the kind of multicultural approach or social justice approach that we find sometimes happening in schools, you know, kind of more of a topical aesthetic approach, versus thinking about just the fact that that we know culture is a predominant force. Right? And people are served in varying degrees by the dominant culture.

Gaby Acosta 32:51

Have you seen the education system have any pushback to the adaptation to transformative SEL?

Amber Pleasant 32:56

What I’ve noticed through working with campus facilitators over a span of years, and honing in on equity, is that they’re taking transformative SEL, or equity centered SEL and running with it. Right. And that, again, is largely largely to do with the work of the cultural proficiency and inclusiveness office in our district. And specifically, Dr. Angela Ward’s leadership, where it gets a little trickier is shifting the larger system above that, you know, within the district, one of the sticking points is that we’re learning the language. Right, many of us are not super practiced at talking about hard things, period, let alone talking about race talking about equity, talking about gender. I mean, these are recognizing that oppression exists, acknowledging systemic oppression and the role that schools and school districts play in, you know, creating trauma, right. And so part of the challenge is just figuring out how do we talk about these these big, big complex ideas that were not practiced and talking about and that bring up a whole lot of feelings? So how do we one, just figure out the language to talk about it? And then how do we also find ways to navigate our discomfort in being able to move through challenging conversations about the shifts and changes that are needed within ourselves and within our system to better support kids?

Gaby Acosta 34:40

So if I’m understanding correctly, there can be social emotional learning without transformative SEL. But transformative SEL is currently being applied intentionally in your district. Is that correct?

Amber Pleasant 34:54

I would say that there are pockets of people who Are deepening the work of transformative SEL? And we have a ways to go, again, because we’re just at a point of learning how to talk about what does this mean, right? Because we’re just beginning to have these conversations just over the course of this year, in particular, I would say, or we’re using the language of transformative SEL, and we’re talking about what is the role of the competencies in transformative SEL, some of the language we’ve been using is equity centered SEL, or SEL is of leverage for equity. So there’s a lot of lingo kind of floating in the air. And we’re trying to orient ourselves around some common understanding of the terms and what they mean for our work. And we don’t want to do that in isolation. We want to build that understanding of what we’re actually talking about, in collaboration with folks that we partner with teachers and families and other departments as well. And so that is slow building work. And it’s particularly challenging in the context of not being able to go into schools in the way that we used to guess the work is happening. It’s just it’s, you know, it’s baby steps.

Gaby Acosta 36:20

Is there anything else that you would like to share around transformative SEL specifically that you think our audience might need to have explained in depth?

Amber Pleasant 36:30

One of the things with transform with a SEL is getting at the root causes of inequities. And that requires a systemic approach, right. And so I think there have been plenty of people who have been developing and understanding of transformative SEL for years because of being a part of a marginalized group, and or dedicating growth and learning to understanding, noticing patterns of inequity and understanding that, hey, we’ve really got to get at these root causes, so that we’re not continuing to perpetuate harm. When SEL is not transformative, we can create more harm. I think, just even in the example of a child who’s upset and is told to manage their emotions, right? or develop a growth mindset, rather than thinking about what are the conditions surrounding this child’s experience in this classroom at this time? And how can I form a learning partnership with this child and their family, to better understand and cultivate their unique gifts and talents, and knowing that in order to see and appreciate whatever individual brains, and then all learning, social and emotional, and how culture is key to how kids make meaning of the world, culture is key to how we all make meaning of the world, right? So if we’re doing SEL to kids, in isolation, have an understanding about our own cultural beliefs, and the cultural beliefs of the people that we’re interacting with. Then, like you said, it’s not just blinders. It’s not fully seeing a child and not seeing how that child is impacted by the system of the classroom of the School of the district of society. And what are the ways in which the teachers, the administrators, the policies, the practices of the institution, what are the ways that all of that interact to counter inequities, or, you know, or perpetuate those?

Gaby Acosta 38:49

We have to take the self awareness piece, and the organizational awareness piece of general emotional intelligence and apply it to the classroom.

Amber Pleasant 38:58

People talk about social awareness in different ways. Right? And so if you’re talking about social awareness, and you’re just thinking about how other people feel around me, and how are they impacted by what’s happening around me, versus thinking about a historical, social and political context? So the national equity project has this article on understanding the lens of systemic oppression. And one of the things that it does really well is it breaks down an understanding of oppression as how does that impact us at an individual level? How does that impact us? interpersonally? Right. And that might be sort of, traditionally how we would think about social awareness is the individual and the interpersonal. But then there’s also the systemic and the policies and the practices of the organization. And so, for me, all of those competencies have to be filtered through an understanding of the lens of systemic oppression because you know, The end we all want to be liberated. And we can’t be liberated if we’re not acknowledging the inequities and the impression that that exists.

Gaby Acosta 40:09

What’s the danger of not acknowledging the systemic or addressing the systemic challenges in our education system, versus thinking about it on a one to one scale, or maybe a one to few scale?

Amber Pleasant 40:23

Well, we just continue to see predictive patterns of who is disproportionately disciplined, suspended, who we continue to see disproportionality of black and brown children being over identified for special education. And, you know, if we’re not examining our own biases, then it’s really easy to continue to just contribute to the subtle racism of low expectations, right. And then we see predictive patterns in terms of literacy rates, and graduation rates, and attendance, because there’s a disconnect, and the heart of it is relationships. But relationships don’t exist in a vacuum. There are always power dynamics. at play, there’s always the dynamics of difference involved in every single interaction that exists. And so if we’re not intentionally addressing how those dynamics of difference how those power dynamics play out in our daily interactions in interrogating them, at an individual, interpersonal, systemic, institutional level, of all those levels that are contributing, you know, we just are contributing, we’re just falling into these patterns that perpetuate inequities. And we just see it happen from year to year to year.

Gaby Acosta 41:48

And now, seven years out since this initiative started in your district, what do you think are the biggest shifts that have happened over time? How did the district transform on all levels,

Amber Pleasant 42:03

and I have to say the district is transforming, right? There’s a campus that I have supported for a long time, seemed like every single time that I walked through the front doors, a child was being restrained. If you’ve ever seen if we’ve ever witnessed a child being restrained by adults, it’s alarming, you know, your heart rate goes up, just if you’re watching. So if you’re that child, or you’re one of the adults involved in that restraint, it’s a traumatic experience. And so we’ve had a lot of conversations about shifting the approach to discipline, right. And that, at the root started with shifting every aspect of the relationship between adults and students. And these were, you know, adults who really loved loved the kids this, this was a really complex situation, the majority of the teachers on that campus were white, the majority of the students were brown and black. And there wasn’t a conversation happening about that. At the time, we began to have those conversations, the steering committee, which is made up of campus coaches, and teachers, and counselor, and I really saw my work as building capacity of that leadership team, a steering committee, that those folks to be able to be the ones who are providing professional learning for their campus to enter into this dialogue, that if I was coming in as an outside person, it wasn’t going to make sense. It wasn’t going to work. They were already dismissive of District folks coming into their campus, it was kind of a protective nature, because they knew their discipline data was bad. They knew that their academic data didn’t look good. There was a lot of sort of a heavy district presence. And it really needed to be the folks on the ground who are making those changes and identifying and defining what changes needed to happen anyway, right. So over time, I would work with the steering committee, and we would design professional learning together, we would co facilitate and then I would slowly back away until they were really facilitating their professional learning on their own over a couple of years, took a couple of years, right? The same time, they were working on campus wide goals, to rethink their approach to discipline to really focus on relationships, they decided to invest in Responsive Classroom training so that every one on their campus would have an opportunity to practice some other ways of being with students, right. And seven years later, this is a campus that is deeply invested in Responsive Classroom that was doing virtual morning meetings and sending those to families all throughout the pandemic, really leading I think, and how they were connecting with families. They’re one of very few campuses in the whole district that has a peer mentoring program where every child is in a pure relationship mentoring relationship with another child in the school received peer mentoring relationships with high schoolers and middle schoolers, even but very rare to see it at an elementary level. And they consistently lead anti bias workshops and send out equity newsletters. And they will also say like, we still have a long way to go, right, we’re not trying to like reach some Pinnacle, right or peak. It’s a constant commitment to learning and growing in community with each other.

Gaby Acosta 45:35

I am so grateful that that’s even a conversation in your district. And it’s something that I know others have struggled educators, in particular, have struggled with in their own schools, let alone their own districts.

Amber Pleasant 45:52

Yeah, I think it’s definitely fair to say the original SEL the way that many people wrote about SEL, and created programs around SEL was white, dominant, and unlimited and understanding systemic oppression. And I’ve been really grateful to notice the shift in the national conversation about social and emotional learning. People like Zaretta, Hammond, Dena Simmons, Gholdy Muhammad, just have contributed greatly to the conversation about the need for this shift. So have folks like Dr. Angela Ward, and members of the equity workgroup, with castle, these are folks that I’m naming that have been, this wasn’t likely woke up one day, and they’re like, Oh, now I see. This is SEL. Right? It was including the right people in the conversation, who live marginalized experiences, and have done the work of understanding oppression at all its levels and not willing to speak to it

Gaby Acosta 46:57

at any recommendation that you might have for how we could approach this better.

Amber Pleasant 47:01

While there’s always an agenda, everything is political, the absence of conversation, is the absence of action is a political statement. Right? When there were ice raids happening in our city, and impacting our students, and our families and staff. And some of us on our team, were saying, Well, look, we know we can, we can root into the social awareness, and recognize that we have to pay attention to what’s happening, the harm that’s happening to people, and we should be providing resources and being supportive. And for some people to say, well, we can’t do that, because that’s a liberal agenda. That’s not our work. That’s not our lane, they have to understand that silence, causes great harm. speaking up, and encouraging people to speak up against injustice is really important. But not saying anything doesn’t mean that you aren’t complicit, right? silences is complicit. And violent. Right? And so those are really hard conversations to have, because sometimes people want to feel neutral. Right? Talking about harm and how we contributed to harm feels bad. You know, it’s interesting, even, you know, way back when I first started learning about SEL, one of the misconceptions was that SEL is all about giggles, and unicorns and glitter and rainbows have good feelings. And so there was a sort of real toxic positivity in terms of how we talked about SEL, how people were understanding the way that we talked about SEL, so the impact was this like toxic positivity, like just be happy, positive vibes only, and not recognizing all of the multitude of feelings that we move through all of the time. Right? And so coming from a place of just acknowledging feelings exist beyond happiness and joy, right? And that is okay, and really necessary for us to experience all of that range of emotions to what’s consider the conditions that contribute to why we feel the ways that we do so I there’s a lot of work to do because there are people well meaning well meaning folks who really believe in social and emotional learning as they understand it to be and don’t see the harm. only see that talking about oppression, creates harm, right makes people feel bad, why would you want to do that and so are really resistant. Then think of it as an agenda. But there’s an overwhelming number of people who are not just having conversations. But following through with action that supports this more transformative and evolving understanding of social emotional learning within a context of understanding historical and social and political contexts of our lives.

Gaby Acosta 50:30

There’s also a piece here right about privilege to be able to not hear the truth about someone’s existence. As somebody who has experienced the world in a certain way, I never had the option, a lot of people definitely have less option than I do now to to be experiencing the way that they walk through life in particular, the first system they experienced outside their family is school. Yes, the way they learn to be split, they’re socialized to the system. If the people that create that system everyday for them are aware of how the world operates for them.

Amber Pleasant 51:10

Yep.

Gaby Acosta 51:10

…Then they’re not going to be able to learn in the most optimized way.

Amber Pleasant 51:14

I think that’s a really that point about the privilege to not talk about something, not attend to ensel dynamics, you know, we have to push back. You don’t talk about it. What is it that you’re trying to protect? Who is it that you’re trying to protect? I know, there’s a conversations that I’ve had in situations where people said to me like, well, I just, it’s really hard to have these conversations. And people really are struggling with this, like, Okay, well, who’s who’s struggling? What are we protecting them from? You know,

Gaby Acosta 51:50

there’s so much here, I feel like we could talk for hours about this. And my sister’s involved in this work on a personal level. And she talks to me about how challenging this work is on the ground. Getting to hear from somebody who gets to see it at every perspective, is really pretty incredible, because just seeing it applied in the classroom is so difficult when you don’t have as much control. And I’ve heard that pain point from her since she became an SEL coach recently, to trying to work with teachers and educators in her region, recognizing that there is a disconnect school by school, and there is a disconnect every hierarchy every single level within the system.

Amber Pleasant 52:35

You know, when I work with teachers, a lot of times what they’ll say is like, or even when I work with principals, they’ll say, Have you met with the associate superintendents Have you met with? You know, are you meeting with the district level leaders leadership at the district level and Board of Trustees, for instance, because to shift a system, ground up, and also you have to be all inclusive. And so I will say teachers have become early adopters and very enthusiastic and we’ve shifted towards transformative SEL largely because of what they’ve shared with us. So much of the work that we’re doing, is because of what we’ve learned from educators in classrooms and from campus leaders.

Hanuman Goleman 53:36

What I’m hearing is that the SEL was happening from both sides, that the staff were learning and becoming more self aware and more aware of the way that they were, their unchecked thoughts and feelings were impacting and affecting and driving the way that they were acting with their students. And then the students were benefiting in the way, Dan, that you were talking about, internally, for their own emotional self control. And so both of those things were happening, I assume. I mean, we like I said, we can’t know. But I think they’re both important.

Daniel Goleman 54:13

I know that the best SEL programs, the ones that work the best include education for the staff, and for the teachers, because you’re really trying to shift the culture of the school. And that sounds like what went on here to one thing about SEL, for kids who are disadvantaged in the ways you assume, was true here. There was a study of kids four to eight, where they assessed cognitive control and whether a kid learned it or not, and then tracked them down in their 30s. And they found that the kids who had it by time they’re eight did better economically and in terms of their health. So there’s a long term advantage kind of leveling up. playing fields. In fact, it was a stronger factor than the wealth of the family that the kids grew up in. We talked about socio economic disparities, and also their IQ. It’s completely independent, which I think is another reason why it’s so important to pay attention to helping kids with their emotional and social abilities, which is what SEL does.

Hanuman Goleman 55:33

I appreciate that amber emphasized the importance of the role of teachers in SEL. Although the change and adoption of SEL is important at all levels. The teachers are the ones adapting and applying it with kids in the classroom and providing feedback about what works in their unique environment. We wanted to explore this further by taking a look at an educators experience in the classroom during 2020. When so much disruption happened to the traditional in person learning environment, can SEL be done well online. Our correspondent Elizabeth Solomon reports in Act Three.

Elizabeth Solomon 56:14

Ben Chase is an educator from Noble High School in North Berwick, Maine. The following excerpt is from an article Ben wrote for the great schools partnership earlier this year. What I love about his story is that it highlights just some of the challenges that have arisen for teachers and students over the past year of virtual schooling, and how you can lean on social emotional learning to create a better classroom experience, especially during this time,

Ben Chase 56:42

Bringing Humanity to the Virtual Classroom: Lessons Learned From My Desk by Ben Chase. A few weeks ago, I found myself almost yelling at my high school students because they weren’t participating in online class. They didn’t appreciate it. My frustration came from a place of love. It was my attempt at holding them to high expectations. But at 8:30 in the morning, it was decidedly not helpful for my half awake students while they were still in bed. Though I can see clearly now that my palpable exasperation certainly wasn’t a recipe for success. It made a lot of sense to me at the time, two classes in a row, I called called student after student in either got silence, or almost worse, the classic. Whatever you’re doing, I feel like I was giving everything I had and still failing hard. Again, and again. Talking into the void and muted students with their cameras off is disheartening, but many of my students are actually in it, the void. To bring them out, I realized that I had to return to one of my early learnings of teaching during this pandemic. She didn’t show up and engage when it feels good to do so when it makes them smile and laugh when they trust that they will leave class in a better mental space than when they arrived. Feeling as an actual feelings is an overlooked part of student engagement right now. That sense of belonging and positive connection to others, say a large and important part of what school has to offer. If our students are not showing up to and engaging in our online classes, maybe it’s because we as teachers have forgotten that the solution is simple. Ensuring that students are happier when they leave our classes than when they arrived. My students keep telling me that it’s hard to do work at home because the environment just isn’t right. What these students seem to be saying that the feeling of connection to us, their teachers, and to their classmates needs to overcome all of the other negative feelings and easy distractions they have at home. Otherwise, our voices are just more noise coming out of another device. The feelings of belonging and connection, which gives our learning communities a center of gravity that pulls students in are essential to overcome that challenge. I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that difficult circumstances and inequities may be the reason many students are disengaged or not showing up at all. For some students showing up on time for class and participating might be an impossibility. These issues of inequity have rightfully been brought to national attention and should stay at the fore until things change. For the purposes of this school year, though, many hardships are students face or what Stanford professors bill Burnett and Dave Evans would call gravity problems. Like gravity. These circumstances are not necessarily solvable, at least in the short term. They just exist as a teacher. However, again, some agency over these circumstances by acknowledging my relationship to them, I can either offer you a reprieve or I can exacerbate the problem. If a student was up late into the night listening to an argument in their home, the last thing they need is me to use a similar tone of voice first thing in the morning. As was the case before the pandemic, and will be after the quality of my teaching matters, and it’s really the only thing I have control over. And just my second year of teaching with my first cut in half by school closure, the struggle is real. And I have an overwhelming amount to learn before. I’m a great teacher. In the four months of school so far this academic year, I have had two weeks of both success and failure. The only difference is in how I was engaging with my students. Either I made it feel good for them to be in class, or I did it. I learned this lesson the hard way. Before I made the pivot, I started to get stressed, a little less funny, and much less fun as a teacher. First, my content wasn’t working for my students, then I wasn’t working for my students. It was a double whammy that all came to a head when I was overcome by self doubt, and internalized belief that I wasn’t good enough to do this work. But thanks to some expert coaching from a mentor, I dug for every scrap of motivation, I had to adjust my practice and content in order to address my newest central question. How could I get my students to once again feel good when they came to my class? Here are the five adjustments that I now intentionally practice every single day.

First, I accept that I am the emotional leader of my class. In the article primal leadership, the hidden driver of great performance, Dan Goleman, and his co authors make a compelling argument that any leader his primary focus should be on emotional leadership. He writes, The leaders mood and behaviors drive the mood and behaviors of everyone else. Their mood is quite literally contagious, spreading quickly, inexorably through the business. As a teacher, I am the leader of my classes mood. Do my students feel lighter, freer and happier when they arrive, and even more so when they leave? accepting the fact that I am the emotional leader has given me the permission that I needed to step away from my computer a little earlier each day. It makes no difference how perfect my lesson plan is, if I’m too tired to be excited about it. Second, I intentionally greet every kid by name when they show up the reality of distance learning for teachers and students alike. It’s very hard to have a sense of the presence of others. Are they there and out there? are they paying attention? Or are they actually asleep. But when students come in, especially the shy ones, it’s a time when I know that I have a moment in which they can feel like their presence is known and appreciated. This might cost me a couple of minutes of class time, but it’s worth it. Third, I allow time for students to connect with one another. One of the biggest bummers of distance learning is that there is no time between classes for the high school social awkwardness and beauty to play out. Sure, my students are texting with their core friend group, and many are seeing each other in person. But all of those acquaintances and budding friendships are put on hold when there is no time for them. In this teaching reality, there’s a clear conundrum because it is impossible to get through content fast enough in a virtual environment. But no amount of content covered matters if most students aren’t paying attention to it. A little informal social time is essential because it makes students look forward to my class. I know this to be true for my own graduate studies online. A breakout room with an extra five minutes to chat and connect adds a measurable value to the experience of class. Fourth, I encourage humor, we’re all in need of a good laugh these days. If you couldn’t tell by now, the problem is that my sense of humor is dry and only provokes a smirk or maybe a chuckle. neither of which I can readily see or hear online. If I want my students to really laugh. I need students to be funny. It can certainly feel like a huge distraction when a student starts to ramp up their humor and take over the online format. When the few kids whose cameras are on are in stitches, there is never a doubt in my mind that it was worth it. Lastly, I end with connection. And the power of moments the heath brothers explained that the end of experiences matter more than just about any other part. We remember experiences by their peak moments and by their endings. If I N class in a way that my students feel connected to one another, the content into me, they will think fondly of the class as a whole. I don’t know the last five minutes every time but I plan for them now. I feel a measurably lighter and more inspired now that I feel like I have found the process that works for me. And I am beyond grateful to work with a team of educators who inspire me daily with their love and kindness for our students and ourselves.

Daniel Goleman 1:04:58

I’m very pleased that what I wrote benefited Ben. Basically, the message is something we can ask ourselves, no matter what interaction we’re having, but particularly for teachers and for leaders, am I leaving people in a better space than before I started? That means that you have an emotional connection and the you as a more powerful person in the relationship are driving the mood of everyone else in the better direction. And you know, the moments kids remember and love, when they think about what they learned or didn’t learn, are moments of kind of a flow where there’s this rapport, where you connect well, and the mood is very, very positive.

Hanuman Goleman 1:05:46

The part of Ben’s recount here that I can really relate to is about his self doubt, and the emotional chaos and overwhelm creating the conditions for these difficult emotions, these destructive emotions to bubble over and to not be as easy to check as when they bubble up when they arise. Because that happens with my children in me, the I mean, with the height of the lockdown at the beginning of the lockdown for this pandemic, I was a real beast, some days, it was very difficult for me to handle my own internal state. And then, you know, at that time, I had a two year old and a four year old, and they also have not yet developed the skills to manage their internal states. So they’re like, luckily, my wife was here, but she was going through a rough time, too. There were like four of us in this house. They were walking around like little emotional monsters, you know. And so, so I can relate to that. And, and slowly, I’m trying to develop some of these tools to manage my own communication. Well, I’m in the midst of a difficult emotion with my children. It’s really interesting to hear someone else’s journey with that and how they’ve approached it. I really appreciate that it’s cool.

SEL is important under normal circumstances and these are not normal times. The difficulties and social strain of hybrid-learning and ongoing uncertainty mean that paying attention to emotional development and wellbeing is even more important. Every caretaker plays an important role in that development. So how, as caretakers, are we showing up? Do we notice when our own habits get in the way of how we want to be? In the next episode Dan talks with Matt Taylor. Matt, a former teacher, is now in the role of professional coach for education leaders. Dan and Matt discuss self-awareness as a key element of working with leadership whether it’s principals, teachers, CEOs, or a leader at any level of an organization.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into SEL Checkout, Triple Focus: A New Approach to Education, a book by Dan Goleman, and Peter Senge. It offers a lens on education that helps students develop awareness of self other and the systems we are a part of. These are the tools that will allow our children to navigate a fast paced world of increasing distraction, and to better understand the interconnections between people, ideas and the planet. You can find this and other SEL resources at keystepmedia.com/shop

Elizabeth Solomon:

Thanks for listening to First Person Plural: EI & Beyond! Subscribe now and sign up for our newsletter to get notified as new episodes are released.

This show is brought to you by our co-hosts, Daniel Goleman and Hanuman Goleman and is sponsored by Key Step Media, your source for personal and professional development materials focused on mindfulness, leadership, and emotional intelligence (EI).

Special thanks to Pippa, whose voice you heard at the top of the show, and to today’s guests Linda Lantieri, Amber Pleasant, and Ben Chase..

For guest bios, transcripts, and resources mentioned in today’s episode, check out our episode notes on our website firstpersonplural.com.

This episode was written and produced by Gabriela Acosta and me, Elizabeth Solomon.

Episode art and production support by Bryant Johnson.

Music in this episode includes

Theme music by…Amber Ojeda.

All other music by Bio Unit

Until next time. Be well.

https://casel.org/

https://casel.org/ @https://twitter.com/caselorg

@https://twitter.com/caselorg @https://www.facebook.com/CASELorg/

@https://www.facebook.com/CASELorg/

Apple Podcasts

Apple Podcasts Google Podcasts

Google Podcasts Spotify

Spotify