I was born in Puerto Cabello, an idyllic seaside city in beautiful Venezuela. I am the daughter of Portuguese immigrants, who like so many others, came from Europe to build a better future in a rapidly developing and modernizing country.

Venezuela received my beloved parents with warmth and joy and a willingness to share prosperity with people who work hard and wanted to become one with their adopted country. My family found their longed for future, and although we were not millionaires, we never missed anything.

Human connection in Venezuela is very close, and it was always easy to find any excuse to meet with friends to celebrate, watch a game or movie together, or simply just enjoy life.

Today, the reality for an immense majority in Venezuela is quite different. Our promising Venezuela crumbled; things we once took for granted are no more. Even basic foodstuffs are scarce, and our citizens are forced to look for them in the trash, taking turns to scavenge for scraps to share.

The streets have lost joy, fear has taken its place, and insecurity has grown by leaps and bounds. Corruption of our political classes is sweeping, and conscious or not, it causes disparity and alienation. Only those who have the resources to pay someone for a passport can dream of a different destiny; maybe a destiny like my parents dreamed of when they left Europe all those years ago.

Those who still find reason to remain in Venezuela, or simply do not have the resources to leave, have accepted that we have water only at unforeseen times, unstable electricity and internet service (when we have it at all), and a diet dependent upon what is available. We receive with certain normalcy the news of a loved one murdered at the hand of an offender (in uniform or not).

Despite the beauty of our landscape and its abundant natural resources, we live in this situation today. This collapse of civilization as I knew and I experienced it caused me to reflect on how my training in Emotional Intelligence might help me and my family through these dark and dangerous days.

In my experience, having Emotional Intelligence made the difference between barely surviving and living courageously during the recent shutdown in Venezuela.

How can Emotional Intelligence be useful when our basic needs are at stake?

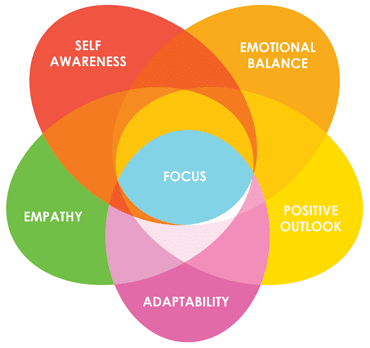

Emotional Self-Awareness

The first thing is to be aware of are your emotions.

For a few minutes every morning and every night I practiced meditation to calm my breathing. During the day, I consciously made the decision to listen to my body and to associate its changes with my emotions. That gave me the opportunity to intervene before my emotions escalated. When my heartbeat accelerated and I felt a certain knot in my chest and throat, I became aware of the presence of fear or anguish, which accompanied me during those days.

I made an effort to identify the trigger of those emotions and reactions in my body. I realized the triggers occurred when I mentally reviewed my plan to face the day without water, without electricity, with uncooked food, and with limited options to acquire basic necessities. During this time the throbbing in my chest was accompanied by the chaos of my thoughts, which gave rise to anguish and fear. Becoming aware of my trigger allowed me to exercise greater control over my reactions while planning my day.

Emotional Balance

Once I utilized emotional self-awareness, which is the foundation of Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence (EI) model, I took advantage of the skills related to the management of my emotions. Emotional balance helped me check my emotions and my reactions to them. This was particularly useful to me, because despite so much pressure, I was able to maintain my own emotional balance and help my family do so as well. I shared with them the importance of observing ourselves during those difficult days, and anticipating the inevitable negative emotions in order to keep ourselves upright. Emotional balance meant that we could pause at the first signs of anguish, fear, or anger, and intervene with a question, a smile, a moment of calm, a talk, and a prayer.

Adaptability

Adaptability enabled me to adjust to our daily struggle and keep my family afloat. Without this competence I would have been unable to recognize that I have the internal resources to deal with these daily challenges.

I try to remember that the conditions are temporarily different, and look for ways to minimize the impact of the whole situation. This allowed me to take off my heels and executive hat and collect water, look for charcoal or firewood, reorganize the housework, and re-plan significant activities.

My intention was not to adapt to being without electricity forever. Adaptability is not conformism; this ability allowed me to adjust to the situation, awakening the possibility to learn from it.

Positive Outlook

In the less stressful moments, I took advantage of positive outlook. In particular, I used a visualization micro-technique which I repeated whenever I considered it necessary. Very intentionally, I focused on the situation I wanted to be in; I imagined it, I gave it color and feeling. I knew that my brain would not know whether this was imaginary or real. This sense of focus gave me more time to talk with my daughters, to sit around a candlelit table game, and pick up books I had begun reading.

Achievement Orientation

I also put together a plan to stick to my current goals. I found a way to charge my phone, and in the moments in which I had telephone service, to update my learning team about my situation, schedule meetings, and anticipate alternatives in case the situation was repeated or extended.

I know that I am fortunate and in a privileged situation. While I focus on my certification, others made use of these skills to find medicine and medical care, or just feed their families and stay hydrated.

Empathy

And among these foundational competencies of Emotional Intelligence, the one that most comforted me and gave me the opportunity to help others was empathy.

By listening without interrupting, without judging, and without anticipating their answers, I was better able to understand what my daughters were thinking and feeling. Empathy allowed me to stay connected and compassionate amid the difficult situation.

Despite competition for basic resources, many of us shared food, water, a generator to charge some appliances, and kitchens at the homes of those who had gas stoves. We also understood that negative reactions often weren’t personal; they were reactions to the whole situation. This understanding in a crisis situation is borne of walking in the shoes of the other and from having the tolerance to be compassionate. In my experience, none of that is possible without empathy.

EI Competencies in Practice

Here’s how you can translate these Emotional Intelligence competencies into concrete actions during a situation like the one we continue to live in Venezuela:

- Develop awareness of your emotions. When you feel fear, anger, happiness, love or another emotion, recognize it. Then stop a moment and ask yourself how you feel, where you feel, and how it manifests in your body. Recognizing your emotions is essential to a strong foundation of Emotional Intelligence.

- Take a break, ideally at the beginning of the day, to practice meditation or an activity that calms you. If you’re new to meditation, try taking at least ten deep and slow breaths.

- Become aware of how you react to each emotion and what your trigger is. For example, if you think about the day’s uncertainties and notice that your breathing starts to accelerate, stop; you just found a trigger. Prepare for how you’ll react the next time you detect that trigger.

- When you detect a strong emotion, don’t react immediately. By taking time to pause, the response to your emotion will be a reaction from your brain’s neocortex, which can override emotional reactions, and not your amygdala, which is automatic and often irrational.

- Adapt to the new conditions. This will allow you the calm needed to build develop a plan. Visualize yourself achieving your plan; your brain will not make distinctions between this happening in reality or in your imagination, take advantage of it.

- When you incorporate new routines, remember to treat yourself with kindness, calculate risks, and allow yourself the time to adjust to the new routine.

- Remember that this situation does not define your life–turn this into a mantra and do not give more power to the situation.

- Practice tolerance and compassion. If you have knowledge of Emotional Intelligence, put it at the service of your connection with others, and lead your interactions with the harmony that only Emotional Intelligence can give us.

Above all, Emotional Intelligence is about recognizing our emotions in order to navigate them and effectively connect with others. EI is not about not feeling our emotions or repressing or controlling them, it is about managing our reactions to our emotions.

One day I found myself with tears in my eyes and I gave myself permission to mourn, to feel my fear, sadness, and anger. I cried for a while until I fell asleep, overcome by the fatigue of that day’s struggle. The next day it dawned on me; by remaining aware of my emotions and my reactions, I had the opportunity to help lead in an emotionally intelligent way, and share my story with my country and the world.