During my study of the relationship between mindfulness and leader effectiveness, 100% of the leaders I interviewed (all having months or years of prior mindfulness training and practice) linked mindfulness to improvement in their personal and professional lives. The majority described this as being significant, often using terms such as “profound,” or “life-changing.” My previous articles on EI draw from this research, exploring the way mindfulness influences each of the 12 Emotional Intelligence competencies, based on interviews with organizational leaders from around the world.

My findings ultimately reveal the following:

Mindfulness influences changes to awareness and behavior that, in turn, play key roles in producing favorable workplace outcomes.

Improved Mental Performance and More Effective Behavior

One of these changes, improved mental performance, was described by participants as having a positive, overarching effect on functions such as decision-making, susceptibility to distractions, and attention. This is not surprising since mindfulness is sometimes defined as meta-awareness, including our ability to non-judgmentally observe where our attention is and is not focused.

This capability can become a “real-time” skill set, taking the form of simultaneous observation of our interaction with others, and our internal reactions to that activity. The leaders I interviewed described this level of awareness, reporting that it provided them with a degree of “mental clarity.” Below are the specific benefits described, and the percentage of participants who reported experiencing them:

- Ability to identify signs of potential conflict (in time to take corrective action) – 90%

- Capacity to more effectively navigate organizational relationships – 88%

- Improved ability to recognize emotional reactions in themselves and others – 86%

- Increased attentiveness and patience with others – 74%

- More productive responses to the emotional states of others – 100%

- Recognition of the negative influence of stress and anxiety – 88%

- Openness to new ideas and input from others – 90%

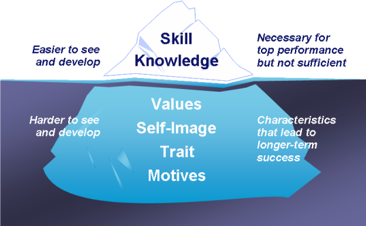

Descriptions of these benefits were provided in the context of how mindfulness helped leaders gain new information about themselves, others, and their workplace culture. This information was then incorporated into their efforts to improve the effectiveness of their interactions with others. As the graphic below illustrates, leaders described an upward spiral of improvement. New insight about self and others fed back into additional, positive changes to beliefs and awareness, which paved the way for more effective behavior.

Real World Examples of Applying Mindfulness at Work

Many of the leaders reported that improved mental performance made them better able to identify and filter out distractions such as emotional reactivity and bias. A senior manager with one of the largest research and publishing firms in the world described this experience in the following way: ” you’re able to calm yourself down and put yourself in a better position to listen to someone… it helps me to be calm and think clearly and to focus…I find I’m able to be composed and organized and clear in my communications.”

Leaders specifically mentioned that mindfulness training helped them be more present when interacting with others. This included a greater ability to monitor what their attention was focused on or being distracted by. They also mentioned becoming better at observing whether or not they were listening carefully, asking relevant questions, and picking up on interpersonal cues and organizational context.

This type of observation, and the value it provides, was well articulated by an executive specializing in global communication and strategy: “(mindfulness) enables you to read other people better and be more sensitive to what’s driving their commentary, their presentation, their behavior…their body language. That makes the connection between the two of you much more on an equal footing basis. So you’re no longer either selling to a position of power, or talking to a position of power. You are in fact exchanging information and dealing with each other on footing that is, at least emotionally, much more equal.”

A new appreciation for the importance of empathy in the workplace was also identified by leaders as a benefit arising from improved mental performance. This resulted from developing a stronger ability to identify and manage the role their own emotional reactions played in their perceptions of others.

A leader who has held executives roles at one of the largest organizations in the world elaborated on this point in the following statement: “It definitely increases your empathy by helping you put yourself in the other person’s shoes. You slow down your responses, and when you sort of look at why that person is reacting in that manner it helps you be more compassionate because the moment you have empathy you start thinking from a very human perspective about the situation and trying to understand what the problem is. And the moment I take that approach I realize that I have solved the problem more effectively.”

What You Can Do to Cultivate Better Mental Performance

Look for opportunities to practice in the workplace, since this will help you develop exactly the type of capabilities needed for improved performance. The following suggestions come from details shared by leaders on this topic during interviews:

- When interacting with others in-person or remotely, put your phone away, turn off your email, web browser, or even your monitor

- Try and continuously monitor where your eyes are focused during interactions with others, as well as your facial expression and what it may be conveying

- Take notes on what you are observing during interactions with others, specifically what they may be expressing through tone, body language, and choice of words

- Regularly ask questions aimed at surfacing misinterpretations

- Take time each day to identify emotional reactions that may have a negative influence on your mental performance

Improved mental performance can be developed through regular practice, not unlike athletic training. There are a variety of software tools and meditation practices available that help strengthen intensity and duration of attention, however, they may not improve your ability to actively observe and more fully understand your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. For this type of development, consider formal mindfulness training, but be sure that the instructor is thoroughly qualified, and plan to make a consistent time commitment if you want results.

Recommended Reading:

Emotional Self-Awareness: A Primer – The first in our series of primers on the Emotional and Social Intelligence Leadership Competencies, with author voices including Daniel Goleman, Richard Boyatzis, Richard J. Davidson, and the author of this article, Matthew Lippincott. The complete collection is also available.

Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body (audio) – New York Times-bestselling authors Daniel Goleman and Richard J. Davidson unveil new research showing how meditation affects the brain.

The Brain and Emotional Intelligence – Daniel Goleman illuminates the state of the art on the relationship between the brain and emotional intelligence, and highlights EI’s practical applications in leadership roles, education, and creativity.