Organizational Awareness is a competency that falls under the domain of Social Awareness, and is one of the twelve learnable capabilities included in the Leadership Competency Model developed by Daniel Goleman and Richard Boyatzis. This competency is empirically linked to leadership performance, and present in leaders with an understanding of the complex relationships and intricacies of their workplace environments, including:

- The values and culture

- Social networks

- Informal structures and processes

- Unspoken rules

Leaders with strength in Organizational Awareness will be conscious of the roles played by relationships, influence, and authority within their organization as well. The leaders I interviewed as part of my study on the impact of mindfulness on leadership effectiveness were able to demonstrate an understanding of these important factors. They also reported having developed a gradually increasing capacity for Organizational Awareness over time, a process they said was enhanced by mindfulness practice.

Developing Organizational Awareness

Your goal should be to build an accurate picture of how and why your organization functions so that you minimize your risk of unintentionally misaligning with the values.

Time spent on this type of development can also help with other competencies such as empathy, influence, and teamwork. This is because Organizational Awareness requires you to collect information about others that can contribute to your ability to more effectively attune to their needs. This form of development requires specific types of social interaction, which will help to expand your social networks and build stronger relationships.

To expand your capacity for this, spend time on both reflection and interaction with others in order to develop and test theories about your workplace. These activities should include:

- Analysis of what organizational factors may have contributed to an event

- Obtaining input on your conclusions from a diverse group of coworkers

- Incorporating what you know about your organizations’ culture when making decisions

- Managing your behavior to ensure alignment with unspoken rules

These activities will also require you to spend more time with coworkers in other departments. This provides you with access to new information contributing to a greater ability to understand the needs of others and the larger value system of your organization. Time spent on these activates also creates an opportunity to develop more meaningful relationships. At every step in this process it is worthwhile to ask questions that help you learn about the needs, day-to-day activities, and personal interests of coworkers. This creates formal and informal channels for gathering information, and cultivates trusting relationships.

Assessing your beliefs about what leadership is, and how leaders function within organizations is important as well.

Many people, including those in leadership roles, have conflicting and inaccurate beliefs about these topics. These beliefs are heavily influenced by the cultures that we grew up in, and are often not supported by research. A great way to enhance your understanding of leadership is to read the book Indispensable by Harvard Business Professor Gautam Mukunda. It explores core beliefs about leadership through in-depth, historical analysis of famous leaders. This story-based approach is highly informative, and makes many potentially confusing concepts accessible to a much larger audience. The primer on Organizational Awareness is another great resource for further understanding and practical skills for developing this competency.

Recommended reading:

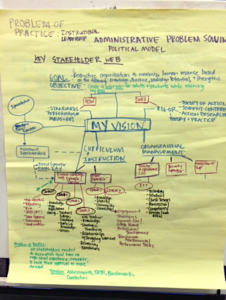

For more examples of Organizational Awareness in action, see Coaching Leaders to Value and Manage Their Organizational Webs.

Our new primer series is written by Daniel Goleman and fellow thought leaders in the field of Emotional Intelligence and research. See our latest release: Organizational Awareness: A Primer for more insights on how this applies in leadership.

Our new primer series is written by Daniel Goleman and fellow thought leaders in the field of Emotional Intelligence and research. See our latest release: Organizational Awareness: A Primer for more insights on how this applies in leadership.

Additional primers so far include: