As the Senior Director of Adaptive Leadership for the Achievement First Charter School Network, I coach for the full range of leadership roles with a focus on emotional intelligence. I’ve been developing leaders for over ten years, but I’d like to tell you a story about how I learned to develop the emotional intelligence competency of Coach and Mentor early on, and how that lead to a refined understanding of the differences between coaching, teaching, and consulting.

The Muddled Approach

David seemed to be struggling to manage his time and take decisive action. This surprised me, as I promoted him from team lead to department manager because of his incredible organization and effective problem solving. So, I dove into developing David’s personal organization system. But that seemed fine, and our work there didn’t improve his performance. David then told me that he just needed a thought partner to solve new kinds of challenges. I shifted to that, assuming that David would learn over time if I lead him to, or just told him, the right answers the first time. Several weeks passed and I realized that David’s task management only got better on the challenges we discussed in our meetings, but not on other issues where I anticipated he’d make progress on his own.

At this point, I wasn’t sure what more I could do for David. There was something going on here that I doubted I could teach him. I began to wonder whether David had the skills and abilities that his role required.

So what went wrong? Ultimately, this is an unfortunate unfolding of events, because I attributed a weakness to David that was actually about my own failure to give him what he needed to grow.

When Teaching and Consulting are Not Enough

Back then I would have told you that I was coaching David, and many managers would agree with me. Since then I have learned from the International Coaching Federation (ICF) and my mentors at the Teleos Institute that I was actually teaching and consulting, not coaching. I have learned in my own work that knowing the difference and being able to match the right approach to the right growth area is critical to developing leaders.

So far in my David story I had been teaching (modeling, practicing, and giving feedback on a skill) and consulting (giving advice and co-creating). I had pushed on his observable skills and knowledge because I assumed that I could SEE David’s obstacle to growth. This would be true if David’s growth area were just a skill gap, but David kept hitting a brick wall. Strong managers who coach know that when someone like David hits a wall with technical skill development, there’s something deeper going on, an obstacle to growth that we can’t see.

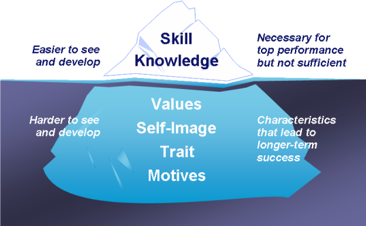

In their training related to Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence model, Korn Ferry Hay Group uses the metaphor of the iceberg to explain that there is a whole set of characteristics we have that are hard to see, and that play a role in our ability to develop new competencies.1

It is easy to see the skills and knowledge that are the “above the surface” part of the iceberg. It’s harder to see values, self-image, and motives. Sometimes these deeply personal characteristics “below the surface” get in the way of our growth. Teaching and consulting alone won’t work when the challenge is below the surface. That’s when we need to coach.

Knowing When to Coach: Technical vs. Adaptive (Or Skill vs. Will)

The concept of technical vs. adaptive challenges has helped me make the right decision about when to coach as a manager. Technical challenges require us to learn new skills and knowledge about something we’ve already got in our wheel-house, and that is consistent with the way we see the world.

Adaptive challenges go beyond skill and knowledge acquisition. They demand a shift in the way we see the world and ourselves. If it’s adaptive, it hits us below the surface at our values, character traits, core motives, and beliefs.2 Quite often, as in David’s case, managers who attack technical skill building quickly discover that the obstacle is actually adaptive. When skill growth stagnates, strong coaches ask themselves a simple question: “Is this a skill issue or a will issue?” When they sense an adaptive or will-related challenge they pivot to coaching. Strong coaches will move back and forth between teaching, consulting, and coaching over time, but they always make a deliberate choice about which hat they are wearing.

A good coach helped me realize that David’s obstacle was an adaptive one. I stopped teaching him how to organize his time and consulting him on technical problems, and I started asking him questions. We dissected specific times when he was getting stuck and I asked him how he was feeling and what was going on in his head in the moment. We discovered that David’s greatest strength, his analytical mind, was turning against him in the face of multiple new challenges and his ensuing feelings of incompetence. When a new challenge came up, David got so in his head about the many potential solutions and his inability to choose that he defaulted to answering email or executing tasks that made him feel successful.

Our coaching shifted to how he could self-manage his limiting emotions and behaviors, and manage his brain so he could settle on one sound decision. I deeply believe that managers can coach. The key is to know when to coach, and to shift our focus to what’s below-the-surface. If we can accept that we don’t have the answers there, then we can facilitate a conversation that helps our people surface their unseen obstacles and tap into their full potential.

To summarize the difference between these three approaches

Teaching is when a manager models, guides practice, observes practice and gives performance feedback, and is appropriate when someone has a skill or knowledge gap.

Consulting is asking guiding questioning, giving advice, and co-creating, and is appropriate when someone needs a thought partner to help solve problems.

Coaching is supporting someone to uncover their internal obstacles and to learn how to manage them, and is appropriate when a manager realizes that skill and knowledge gaps are not the primary obstacle to performance.

Recommended Reading:

In Coach and Mentor: A Primer, Daniel Goleman, Matthew Taylor, and colleagues introduce Emotional Intelligence and dive deep into the Coach and Mentor Competency, exploring what’s needed to develop this capacity in leadership.

In Coach and Mentor: A Primer, Daniel Goleman, Matthew Taylor, and colleagues introduce Emotional Intelligence and dive deep into the Coach and Mentor Competency, exploring what’s needed to develop this capacity in leadership.

In a relatively short read, the authors illustrate the valuable skills needed to foster the long-term learning or development of others by giving feedback and support.

See the full list of primers by topic, or get the complete Emotional Intelligence leadership competency collection!

References:

- Hay Group. “What is a Competency” from Hay Group Accreditation Training Presentation (Boston, MA, 2013).

- Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linsky, (2002) Leadership on the Line: Staying Alive through the Dangers of Leading. (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2002).